Resident takeover on psychodermatology, plus a cure for vitiligo?

- Af

- Episode

- 12

- Published

- 29. aug. 2019

- Forlag

- 0 Anmeldelser

- 0

- Episode

- 12 of 100

- Længde

- 23M

- Sprog

- Engelsk

- Format

- Kategori

- Personlig udvikling

Psychiatric disease is seen in 30%-60% of dermatology patients. In this special resident takeover of the podcast, three dermatology residents – Dr. Elisabeth Tracey, Dr. Julie Croley, and Dr. Daniel Mazori – talk about the challenges of treating patients with both psychiatric and dermatologic disease. "In some instances, although ideally, we would like to refer [patients to a mental health professional], we do have to develop good skills during our training to be well equipped to handle these cases," explains Dr. Croley. Beginning at 4:29, they discuss common psychiatric disorders seen by dermatologists, appropriate therapies, and strategies for building a strong rapport with these patients prior to referral. We also bring you the latest dermatology news and research. Recent progress in vitiligo treatment might be heading to vitiligo cure Clinical trials are now actively being planned to target interleukin-15, a cytokine thought to be essential for maintaining memory T cells. In murine models, this approach led to rapid and durable repigmentation without apparent adverse effects. Dermatologists lack training about skin of color The results of a small survey argue for enhanced training in treating patients with skin of color, an emphasis on culturally sensitive and competent care, and greater diversity in the dermatology workforce. Things you will learn in this episode: • Dermatologists often see psychiatric disease in two forms: a condition that is primary and drives a cutaneous disease or a condition that is comorbid or secondary to a dermatologic disorder. • Delusional infestation (also known as delusions of parasitosis) is a common primary condition in dermatology. Patients with delusional infestation have a fixed false belief that an organism or other nonliving matter is present in or under the skin, which they may bring to the office in a matchbox as proof of infestation (known as the matchbox sign). Dr. Mazori adds, "Now that about 80% of Americans own smartphones, instead of the matchbox sign, I've seen patients increasingly present with photos of the specimens." • Obsessive-compulsive disorder and other related disorders represent a broad category of primary conditions, including body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), olfactory reference syndrome, excoriation disorder, trichotillomania, and trichophagia. • An estimated 12% of dermatology patients have BDD, which presents more commonly in cosmetic dermatology. In the general dermatology population, BDD occurs at the substantial rate of 7%. • In patients with dermatitis artefacta, a condition in which the individual has deliberately self-afflicted skin lesions, the motive for the behavior is unconscious. This illness should be distinguished from malingering, in which patients have a conscious goal of secondary fame. • Useful treatment modalities for primary neurodermatoses include antidepressants, antipsychotics, and cognitive-behavioral therapy. • Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a first-line treatment of BDD and also may be useful for olfactory reference syndrome. • The antipsychotics risperidone and olanzapine have achieved full or partial remission in two-thirds of delusional infestation cases. • A mental health referral is warranted for patients who have a psychiatric condition secondary to or comorbid with a skin disorder. • Avoid referring patients in the first visit. Build a strong therapeutic alliance or rapport to gain their trust before making a referral. • Consider focusing on symptomatic treatments for patients. For patients with delusions of parasitosis, offer strategies to reduce skin picking. • If a patient brings a sample of a parasite, examine it and then review the results in a matter-of-fact way. "Always try to be sympathetic," advises Dr. Mazori. "Even though we shouldn't confirm their delusions, we can still acknowledge that they're experiencing symptoms that are real." • For pediatric patients, interview parents/guardians to elicit history and perhaps an underlying cause of a psychiatric component. • A psychiatry-dermatology multidisciplinary clinic can help destigmatize referral to a mental health professional. "The dermatologist sees a patient with a psychiatrist," explains Dr. Tracey. "The patient feels like they are coming to see the dermatologist. Then we tell the patient [that] everyone in this clinic sees both of these providers and that's the way we are able to help these patients see a psychiatrist." If you know someone in crisis, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255. Hosts: Nick Andrews, Carol Nicotera-Ward Guests: Elisabeth (Libby) Tracey, MD (Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Ohio); Julie Ann Amthor Croley, MD (The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston); Daniel R. Mazori, MD (State University of New York, Brooklyn). Show notes by Jason Orszt, Melissa Sears, Kathy Scarbeck You can find more of our podcasts at http://www.mdedge.com/podcasts. Email the show: podcasts@mdedge.com Interact with us on Twitter: @MDedgeDerm

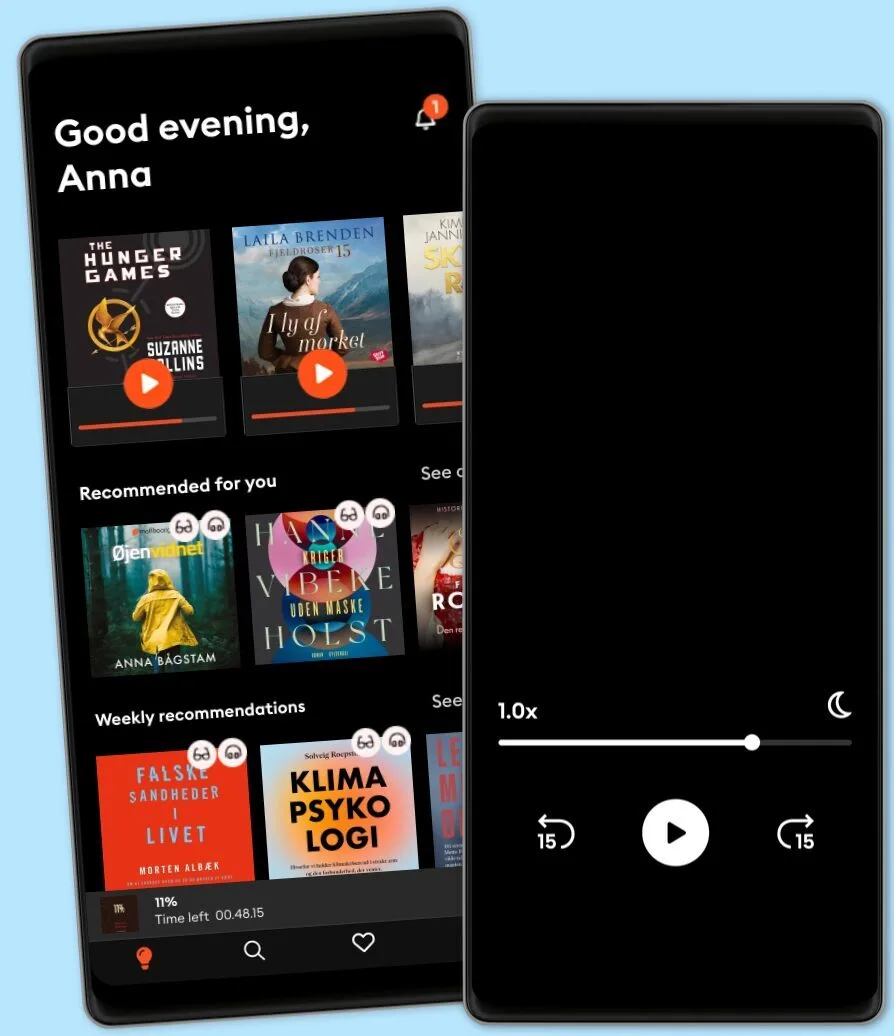

Lyt når som helst, hvor som helst

Nyd den ubegrænsede adgang til tusindvis af spændende e- og lydbøger - helt gratis

- Lyt og læs så meget du har lyst til

- Opdag et kæmpe bibliotek fyldt med fortællinger

- Eksklusive titler + Mofibo Originals

- Opsig når som helst

Other podcasts you might like ...

- Ask a ScientistScience Journal for Kids

- Story Of LanguagesSnovel Creations

- Rise With ZubinRise With Zubin

- Quint Fit EpisodesQuint Fit

- 'I AM THAT' by Ekta BathijaEkta Bathija

- Eat Smart With AvantiiAvantii Deshpande

- Intrecci - L’arte delle relazioni Ameya Gabriella Canovi

- Chillin' with ICECloud10

- Minimal-ish: Minimalism, Intentional Living, MotherhoodCloud10

- Talk To Me In KoreanTTMIK

- Ask a ScientistScience Journal for Kids

- Story Of LanguagesSnovel Creations

- Rise With ZubinRise With Zubin

- Quint Fit EpisodesQuint Fit

- 'I AM THAT' by Ekta BathijaEkta Bathija

- Eat Smart With AvantiiAvantii Deshpande

- Intrecci - L’arte delle relazioni Ameya Gabriella Canovi

- Chillin' with ICECloud10

- Minimal-ish: Minimalism, Intentional Living, MotherhoodCloud10

- Talk To Me In KoreanTTMIK

Dansk

Danmark