Romanian Orphanage Babies: 21 Years On

- Af

- Episode

- 23

- Published

- 11. okt. 2011

- Forlag

- 0 Anmeldelser

- 0

- Episode

- 23 of 297

- Længde

- 28M

- Sprog

- Engelsk

- Format

- Kategori

- Personlig udvikling

After the fall of Nicolai Ceausescu in Romania, news of how babies and children were treated in Romanian orphanages horrified the world.

Images of infants, silent and malnourished, rocking in their cots, hosed down with cold water, prompted an outburst of collective outrage and thousands of would-be parents rushed to adopt.

But little was known then, in 1990, about the long-term effects of such extreme, early deprivation: how would the babies and toddlers who had been denied basic human contact and care, adapt and recover when they were transfered to their new, loving and caring families?

Twenty one years on, and scientists who have been tracking the progress of these children in the English and Romanian Adoptees study, have made some astonishing discoveries.

Claudia Hammond talks to Professor Sir Michael Rutter and his team about this "unique and natural experiment", which enabled scientists to pinpoint, exactly, when severe deprivation ended and good parenting began.

She discovers just how quickly these babies and toddlers caught up with their English peers and hears encouraging evidence about the capacity of human beings to recover from the most appalling early treatment.

But she finds out too, that for some of these children, the sobering reality is that their impairments appear to be long-lasting.

Cindy and Anthony Calvert from Northallerton in North Yorkshire describe bringing 18-month old Adi back from an orphanage in the north of Romania. She was dehydrated, with tiny, wrinkled, dry hands and a terror of flies. She flourished in her new home, but was so fearful of being thirsty, she would drink water whenever she could. And her early experience of being held under freezing cold water to wash her, she admits, has left her with a life-long fear of swimming.

And Will Moult, now 21 years old, who's training to be a primary school teacher, tells Claudia about his early life in one of Romania's most notorious institutions, Orphanage Number One, in Bucharest. He knows he had very little human contact as a baby, until he was adopted and brought to London when he was 18 months old. Uncomforted and alone, he'd rubbed a bald patch on the back of his head from holding onto the bars of his cot. But now Will wants to write a book about his experiences in order to help other, adopted children.

Both Adi and Will are both testament to the remarkable resilience shown by so many of the babies and toddlers who were adopted from these Romanian institutions. And it's finding out why children like these appear to have overcome the most traumatic of early years, while others continue to struggle, that makes the long-term ERA study so important.

Producer: Fiona Hill.

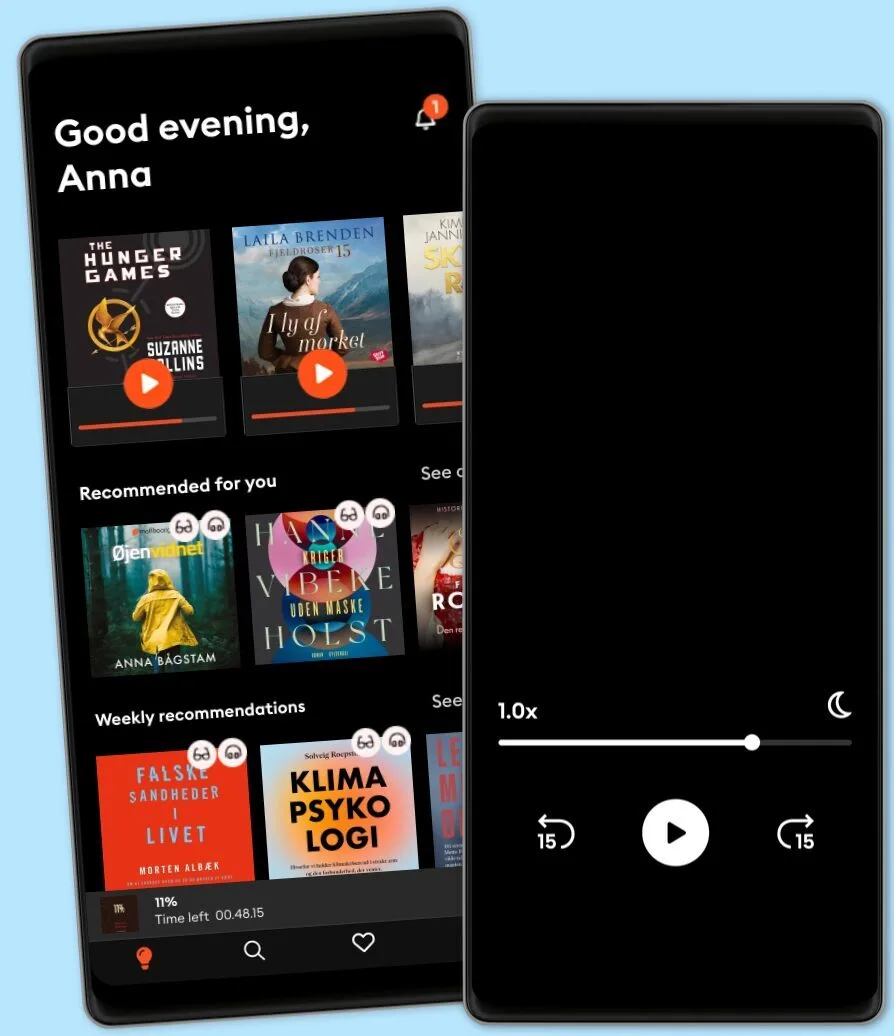

Lyt når som helst, hvor som helst

Nyd den ubegrænsede adgang til tusindvis af spændende e- og lydbøger - helt gratis

- Lyt og læs så meget du har lyst til

- Opdag et kæmpe bibliotek fyldt med fortællinger

- Eksklusive titler + Mofibo Originals

- Opsig når som helst

Other podcasts you might like ...

- Ask a ScientistScience Journal for Kids

- Story Of LanguagesSnovel Creations

- Rise With ZubinRise With Zubin

- Quint Fit EpisodesQuint Fit

- 'I AM THAT' by Ekta BathijaEkta Bathija

- Eat Smart With AvantiiAvantii Deshpande

- Intrecci - L’arte delle relazioni Ameya Gabriella Canovi

- Chillin' with ICECloud10

- Minimal-ish: Minimalism, Intentional Living, MotherhoodCloud10

- Talk To Me In KoreanTTMIK

- Ask a ScientistScience Journal for Kids

- Story Of LanguagesSnovel Creations

- Rise With ZubinRise With Zubin

- Quint Fit EpisodesQuint Fit

- 'I AM THAT' by Ekta BathijaEkta Bathija

- Eat Smart With AvantiiAvantii Deshpande

- Intrecci - L’arte delle relazioni Ameya Gabriella Canovi

- Chillin' with ICECloud10

- Minimal-ish: Minimalism, Intentional Living, MotherhoodCloud10

- Talk To Me In KoreanTTMIK

Dansk

Danmark