Judith Bunbury on the shifting River Nile in the time of the Pharaohs

- Af

- Episode

- 264

- Published

- 14. sep. 2022

- Forlag

- 0 Anmeldelser

- 0

- Episode

- 264 of 346

- Længde

- 28M

- Sprog

- Engelsk

- Format

- Kategori

- Fakta

Think Sahara Desert, think intense heat and drought. We see the Sahara as an unrelenting, frazzling, white place. But geo-archaeologist Dr Judith Bunbury says in the not so distant past, the region looked more like a safari park.

In the more recent New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt, from around 3.5 thousand years ago (the time of some of Egypt’s most famous kings like Ahmose I, Thutmose III, Akhenaten, Tutankhamun and queens like Hatshepsut) evidence from core samples shows evidence of rainfall, huge lakes, springs, trees, birds, hares and even gazelle, very different from today.

By combining geology with archaeology, Dr Bunbury, from the department of Earth Sciences at the University of Cambridge and Senior Tutor at St Edmund’s College, tells Jim Al-Khalili that evidence of how people adapted to their ever-changing landscape is buried in the mud, dust and sedimentary samples beneath these ancient sites, waiting to be discovered.

With an augur (like a large apple corer), Judith and her team take core samples (every ten metre sample in Egypt reveals approximately 10,000 years of the past) and then read the historical story backwards. A model of the topography, the environment, the climate and the adapting human settlements can then be built up to enrich the historical record.

The core samples contain chipped stones which can be linked directly to the famous monuments and statues in the Valley of the Kings. There are splinters of amethyst from precious stone workshops, tell-tale rubbish dumped in surrounding water as well as pottery fragments which can be reliably time-stamped to the fashion-conscious consumers in the reign of individual Pharaohs.

The geo-archaeological research by Judith and her team, has helped to demonstrate that the building of the temples at Karnak near Luxor, added to by each of the Pharaohs, was completely dependent on the mighty Nile, a river which, over millennia, has wriggled and writhed, creating new land on one bank as it consumes land on another. Buildings and monuments were adapted and extended as the river constantly changed course.

And Judith hopes the detailed, long-range climate records and models we already have, can be enriched with this more detailed history of people, their settlements and their activities within a changing landscape and this will contribute to our ability to tackle climate change.

Producer: Fiona Hill

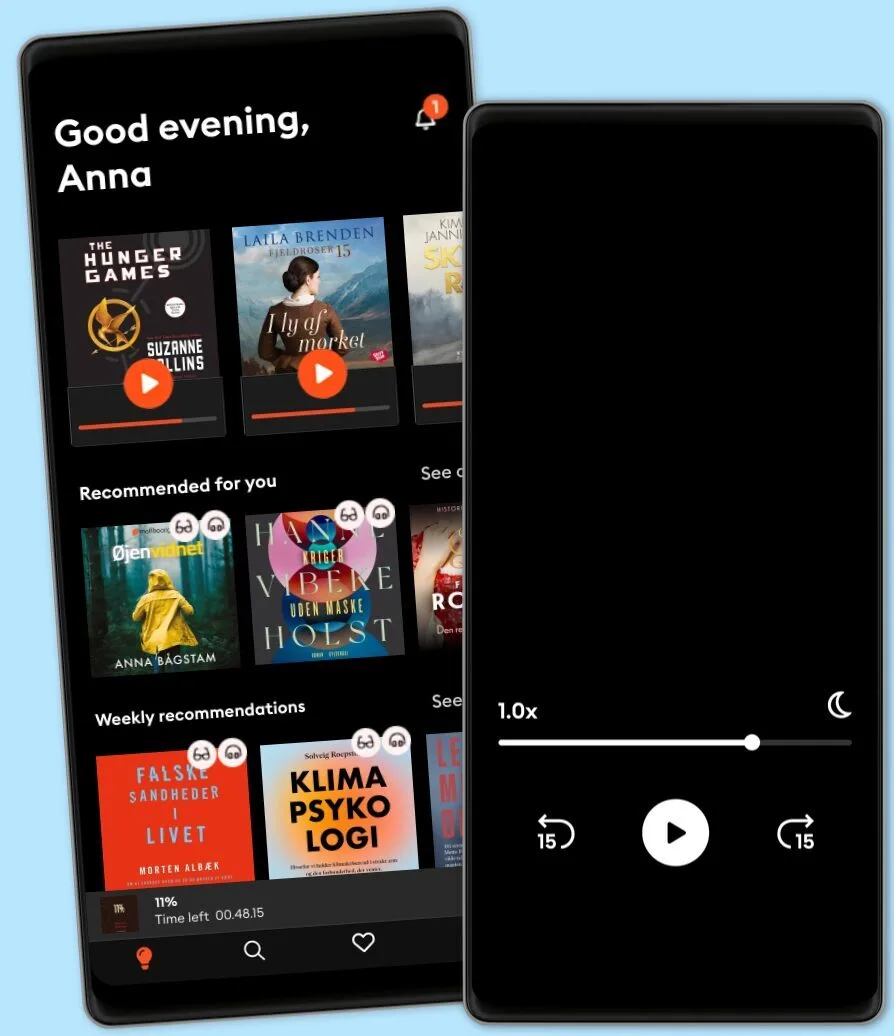

Lyt når som helst, hvor som helst

Nyd den ubegrænsede adgang til tusindvis af spændende e- og lydbøger - helt gratis

- Lyt og læs så meget du har lyst til

- Opdag et kæmpe bibliotek fyldt med fortællinger

- Eksklusive titler + Mofibo Originals

- Opsig når som helst

Other podcasts you might like ...

- M’usa, con l’apostrofo. Le donne di PicassoLetizia Bravi

- FC PopCornFilm Companion

- The Big StoryThe Quint

- DiskoteksbrandenAntonio de la Cruz

- Dragon gateEdith Söderström

- En amerikansk epidemiPatrick Stanelius

- En värld i brand: Andra världskriget och sanningenAnton Vretander

- FamiljenFrida Anund

- Hagen-fallet: Spårlöst försvunnenAntonio de la Cruz

- HelikopterpilotenVictoria Rinkous

- M’usa, con l’apostrofo. Le donne di PicassoLetizia Bravi

- FC PopCornFilm Companion

- The Big StoryThe Quint

- DiskoteksbrandenAntonio de la Cruz

- Dragon gateEdith Söderström

- En amerikansk epidemiPatrick Stanelius

- En värld i brand: Andra världskriget och sanningenAnton Vretander

- FamiljenFrida Anund

- Hagen-fallet: Spårlöst försvunnenAntonio de la Cruz

- HelikopterpilotenVictoria Rinkous

Dansk

Danmark