Excesses of rain

- Af

- Episode

- 279

- Published

- 3. okt. 2024

- Forlag

- 0 Anmeldelser

- 0

- Episode

- 279 of 334

- Længde

- 36M

- Sprog

- Engelsk

- Format

- Kategori

- Fakta

As we were putting the finishing touches to last week’s Science in Action, the US National Weather Service was warning of Hurricane Helene’s fast approach to the Florida coast – alerting people to ‘unsurvivable’ storm surges of up to 6 metres. But the category 4 storm powered, as forecast, far past the coast and into the rugged interior of Tennessee and the Carolinas. 150 billion tonnes of rainfall are estimated to have been dumped there, with devastating consequences for the towns and villages snuggled into the deep-cut valleys of the region. Bloomberg says the event could cost $160 billion. Extreme warmth in the Gulf of Mexico helped fuel the hurricane, and within a few days Berkeley climatologist Michael Wehner had computed the fingerprint of climate change on the event.

The journal Nature published this week a study estimating the true number of casualties of hurricanes like Helene – not just those registered in the immediate aftermath, deaths caused by the instant trauma, but those in the months, even years, that follow, because of the disruption to lives and infrastructure. Rachel Young of Stanford University was herself surprised by the scale of harm her calculations revealed.

At least the dams held in North Carolina during Helene, although the sight of torrents of water gushing down the protective spillways at the peak was fearsome to see. A year ago, the two dams upstream of the Libyan port Derna both failed during Storm Daniel – ripping out the heart of the city and claiming at least 6000 lives. We reported what we could at the time here on Science in Action. But a World Bank study on the disaster reported back to an international dam conference in India this week a more detailed investigation – though the fractious politics of Libya put constraints on their work. Climate change was a massive part – normal monthly September rain in the area is 1.5 mm – but over 200 mm, maybe 400, fell on the hills behind Derna the night of the 10th. But it was the report of independent engineer Ahmed Chraibi that interested Science in Action – on the condition of the two dams, one just on the edge of the city, the other larger one 15 km upstream. He confirmed these had been built, in the 70s, for flood protection not to store water, but were in a shocking state long before last year’s cataclysm.

You’ve not been paying attention here in the past 5 years if you haven’t learned how clever our immune system is in recognising viruses that invade our bodies. Different arms of the system like antibodies and white blood cells can take on the viruses directly, or kill infected cells to stop the infection spreading further. But it’s slow to respond to new infections, which is why our pharmacies also stock antivirals, small molecules which also lock onto components of viruses to stop them replicating. Too often though, they’re not as effective as we’d like. Flu antivirals for example work only if you catch the infection very early. So I was intrigued to read in the Proceedings of the National Academy this week of a new kind of drug that is like an antiviral, but gets the immune system to do the hard work. Imrul Shahria reckoned there are all kinds of antibodies and immune cells floating through our tissues not doing much, but that could be tricked into tackling flu infections – with a little molecular deception. He's effectively hacked the flu antiviral zanamivir which locks onto the neuraminidase protein – the N – of flu viruses, and given it immune superpowers.

Presenter: Roland Pease Producer: Alex Mansfield Production co-ordinator: Andrew Rhys Lewis

(Photo: Hurricane Helene causes massive flooding across swaths of western North Carolina. Credit: Melissa Sue Gerrits/Getty Images)

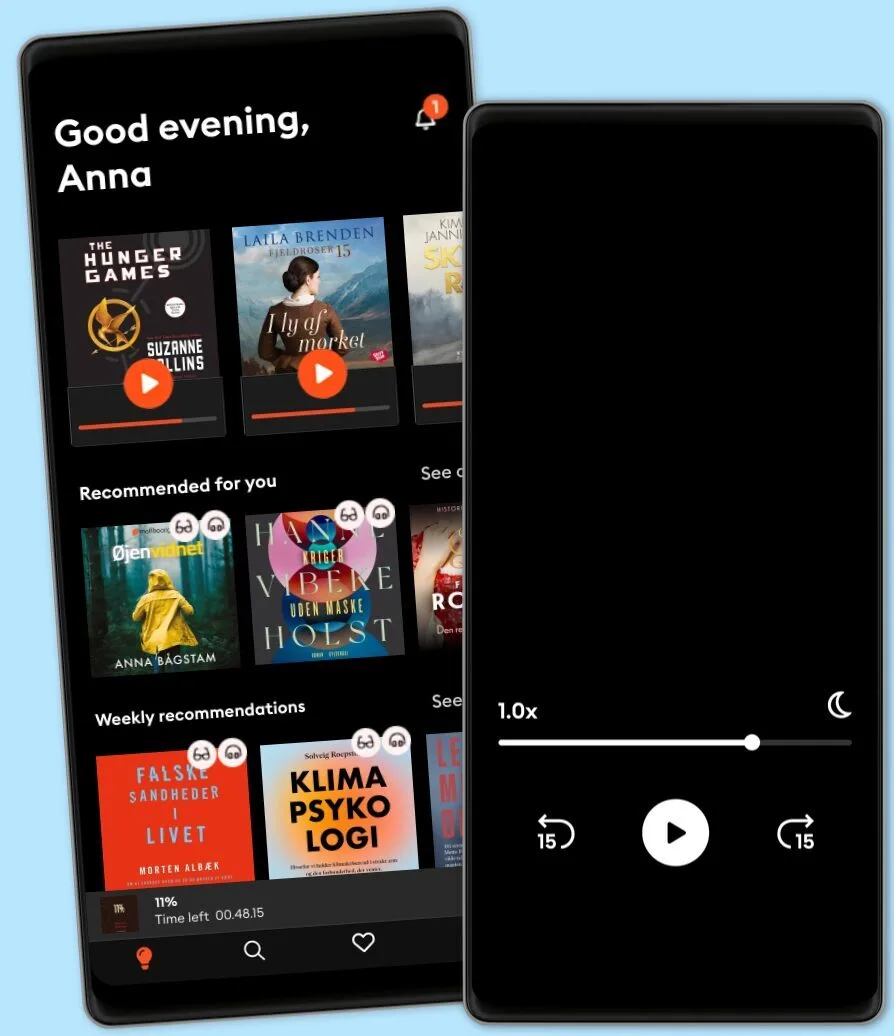

Other podcasts you might like ...

- M’usa, con l’apostrofo. Le donne di PicassoLetizia Bravi

- FC PopCornFilm Companion

- The Big StoryThe Quint

- DiskoteksbrandenAntonio de la Cruz

- Dragon gateEdith Söderström

- En amerikansk epidemiPatrick Stanelius

- En värld i brand: Andra världskriget och sanningenAnton Vretander

- FamiljenFrida Anund

- Hagen-fallet: Spårlöst försvunnenAntonio de la Cruz

- HelikopterpilotenVictoria Rinkous

- M’usa, con l’apostrofo. Le donne di PicassoLetizia Bravi

- FC PopCornFilm Companion

- The Big StoryThe Quint

- DiskoteksbrandenAntonio de la Cruz

- Dragon gateEdith Söderström

- En amerikansk epidemiPatrick Stanelius

- En värld i brand: Andra världskriget och sanningenAnton Vretander

- FamiljenFrida Anund

- Hagen-fallet: Spårlöst försvunnenAntonio de la Cruz

- HelikopterpilotenVictoria Rinkous