How to Create a Micro-Startup in Japan – Patrick McKenzie

- Af

- Episode

- 75

- Published

- 20. feb. 2017

- Forlag

- 0 Anmeldelser

- 0

- Episode

- 75 of 256

- Længde

- 48M

- Sprog

- Engelsk

- Format

- Kategori

- Økonomi & Business

More than a few people dream of coming to Japan, starting an online business that gives you financial freedom and leaves you with enough free time to study the language travel and just enjoy Japan.

I know that sounds like the opening to some terrible multi-level marketing pitch, but today we site down and talk with someone who has done exactly that — twice.

Patrick McKenzie came to Japan more than 15 years ago and after enduring the soul-crushing boredom that is the life of a Japanese programer, he took maters into his own hands, left his job and began developing software products that he sold and supported all over the world the world from his home in the Japanese countryside.

It turns our that life was not as idillic or as simple as it seems, but there are some important lessons learned and a great story to be told.

I think you’ll enjoy this one.

Show Notes for Startups

What it's like working as a developer at a Japanese company The 30-year career plan Japanese companies have for their employees Why Japanese developers don’t start side businesses Why it's smart to focus on the foreign market when selling software from Japan What's the wrong way to generate a startup idea Why running a micro-startup can be more rewarding than getting investment What made Patrick give it all up and get a day job Why you need to develop the ability to do arbitrary hard things How to make failure a part of life in Japan, and why that would be a good thing

Links from the Founder

Patrick runs the Kalzumeus blog Check out some of Patrick's (aka patio11) prolific writing at Hacker News Stripe's Atlas Program Check out the Kalzumeus podcast, and tell Patrick to make more of them

[shareaholic app="share_buttons" id="7994466"] Leave a comment

Transcript from Japan Disrupting Japan, episode 74.

Welcome to Disrupting Japan, straight talk Japan’s most successful entrepreneurs. I’m Tim Romero, and thanks for joining me.

One of the things I enjoyed most about making Disrupting Japan, is not only do I get a chance to sit down and talk with some of the most innovative people in Japan, but I hear from people all over the world who are thinking about bringing their company to Japan, or who are deeply involved in the startup scene in their own country, or who just have a love of Japan and enjoy hearing about startups and how things are changing here.

I also get a pretty steady stream of inquiries from listeners with a very specific Japan-focused dream. There are a lot of developers all over the world who want to move to Japan, maybe move to a Japanese company, study the language, and then start some kind of internet business that would give them the financial independence and the freedom to just live your life in Japan. Well, if that sounds appealing, I’ve got a treat for you today.

Today, we’re going to sit down and talk with my friend, Patrick McKenzie, and we’re basically going to give you a blueprint for doing exactly that. I’ll warn you in advance, it might not be as easy as you think it is, or as rewarding as you imagine it might be, and in fact, in the end, Patrick left that life behind. Before he did that, however, he created not just one, but two successful online businesses, that he ran from the comfort of the Japanese countryside. Now, you’ve probably never heard of either of Patrick’s companies, but he’s a more important part of the Tokyo startup ecosystem than he likes to let on. He’s an advisor, a connector, and someone whose name just keeps popping up in Tokyo’s startup scene, and he has a really amazing story to tell.

So let’s hear from our sponsors and get right to the interview. [pro_ad_display_adzone id="1411" info_text="Sponsored by" font_color="grey" ]

[Interview] Tim: I’m sitting here with Patrick McKenzie of Stripe and of Kalzumeus software, and the illustrious Kalzumeus podcast, as a matter of fact. You’re really a unique figure in the startup ecosystem in Japan and you’ve done something that I think a lot of our listeners dream about doing, which is running two companies on your own here. Your ideas, your marketing, your coding, and bringing them to fruition, and so thanks for sitting down and talking with us today.

Patrick: Thanks so much for having me, Tim. Hidey-ho, everybody, I’m Patrick McKenzie, better known as Patio11 on the internets. Micro tip for everybody: memorize a self-intro that is one sentence long and then you can just play it on every podcast, from now to eternity. I don’t know if I’m a very important person, but I have a less than common life story, so people apparently like hearing it.

Tim: Well something that I think should be more common. You did what a lot of people want to do. You became a micro-startup. You went from idea, to code, to product, not once, but twice, in Japan. In fact, you were living in the countryside while doing it, so literally, doing your own business from anywhere. Before we really dig into the mechanics of those companies, let’s back up and talk about you for a bit. Why Japan?

Patrick: I have an odd answer to this question. I grew up with my father and every day, as our father-son bonding activity, we would read the Wall Street Journal together. And when I was studying engineering in school, the Wall Street Journal was very insistent—this was back in the early 2000s. All of the engineering jobs were going to India and China, so I was getting a lot of parental pressure, “Go get a W-2 job at a nice, big megacorp, something which is safe and stable, with healthcare,” and my inaccurate assessment of the world, from my perch in St. Louis at the time, was that basically only existed in the United States at Microsoft, so I wanted to get a job at Microsoft, but I didn’t think I was the sharpest knife in the coding drawer, so I thought, “If I could combine a language that was commercially reasonable for software development, with the actual skill of doing software development, then Microsoft would have to give me a job, as like the product manager of X country Excel. And if I did that, I would be only competing against not 100,000 people who were graduating in India and China every year, but only the small subsection who had mastered the same language and were also fluent in English. So I asked my university, “Can you give me a list of every language the university teaches?” I went down the list on how many billions of dollars of software does this country make and how many billions of dollars of software do they buy? And Japan was number one on this by a longshot. So I immediately signed up for Japanese 101 and I think about one hour into learning the Japanese language, I was like, “Yep, this is clicking with me. I’m totally going to major in this.” So I majored in that and in engineering and then when I graduated, I was like, “Can I, in good conscience, go to Microsoft right now, and say, ‘You should make me the product manager of MS Excel Japanese version.’” I thought, “Well, I know nothing about anything and my Japanese is good enough to have a conversation, but probably not good enough to lead a project management meeting.”

Tim: Actually, the idea of combining engineering with another skill is a really good one for anyone, whatever that other skill or other passion happens to be. Did you try to market yourself? Did you try to get a job combining those two skills straight out of college? Or were you really kind of headed for Japan at this point.

Patrick: I was terrible at this. I was actually—randomly met someone who it would be professionally advantageous to know if that was the career past plan, and when he heard engineering degree plus some level of Japanese conversational fluency, he asked me to apply to his company on the understanding that he would immediately be able to say yes to the application. And I heard that and did not take action on it because I was worried about it being too much. Meanwhile, I could just send him an e-mail saying, “Hey, I graduated now. Can I have that job you promised me?” When I graduated, I thought my Japanese not sufficient to run an engineering meeting in Japan right now, so I will go over to Japan after graduation, work as a translator for a few years to firm up my business Japanese, and them come back and get a job with Microsoft, was the plan.

Tim: Okay, it seems like being in St. Louis, it would actually be harder to get a job as a translator in Japan than it would be to get a job as a product manager at a software company in America.

Patrick: Yeah, you would think that, right? I think this is one of the many times in life where people don’t have a great idea for what is easy and what is hard. They just have an idea for what is like the well-trodden path and what is not the well-trodden path, at Washington University, which was where I was going to school. One well-trodden path was applying to the JET program. There is an A4 sheet of paper that you just put your name on and boom, that takes off—

Tim: A clear path from A to B.

Patrick: Yeah, a clear path from A to B. I’m like, “Oh, I will apply to the clear path from A to B,” and applied to the JET program. They assigned me as a coordinator for international relations, prefecturally sponsored technology incubator and Gifu prefecture. If you’re not too familiar with the JET program, they do 3 things: the big one is they send people without much Japan experience or knowledge of the Japanese language to be ALTs, Assistant Language Teachers at Japanese schools, to have a foreigner with native pronunciation of English teaching there. And then their much smaller thing is they place translators and interpreters at a variety of governmental and quasi-governmental organizations.

Tim: But at this point, your Japanese wasn’t good enough to be a translator, right? So you were going in to be an English teacher?

Patrick: No,

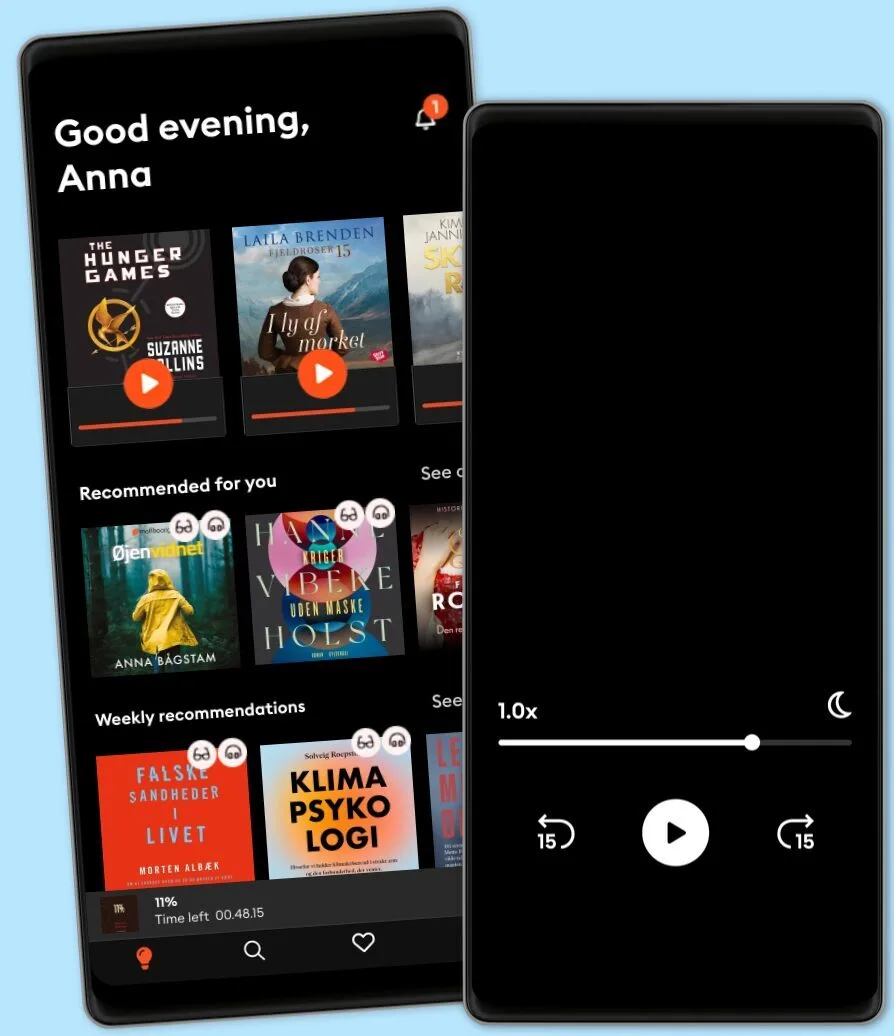

Lyt når som helst, hvor som helst

Nyd den ubegrænsede adgang til tusindvis af spændende e- og lydbøger - helt gratis

- Lyt og læs så meget du har lyst til

- Opdag et kæmpe bibliotek fyldt med fortællinger

- Eksklusive titler + Mofibo Originals

- Opsig når som helst

Other podcasts you might like ...

- The Journal.The Wall Street Journal & Spotify Studios

- The Can Do WayTheCanDoWay

- 1,5 graderAndreas Bäckäng

- Redefining CyberSecuritySean Martin

- Networth and Chill with Your Rich BFFVivian Tu

- Maxwell Leadership Executive PodcastJohn Maxwell

- Mark My Words PodcastMark Homer

- Ruby RoguesCharles M Wood

- EGO NetCastMartin Lindeskog

- The Pathless Path with Paul MillerdPaul Millerd

- The Journal.The Wall Street Journal & Spotify Studios

- The Can Do WayTheCanDoWay

- 1,5 graderAndreas Bäckäng

- Redefining CyberSecuritySean Martin

- Networth and Chill with Your Rich BFFVivian Tu

- Maxwell Leadership Executive PodcastJohn Maxwell

- Mark My Words PodcastMark Homer

- Ruby RoguesCharles M Wood

- EGO NetCastMartin Lindeskog

- The Pathless Path with Paul MillerdPaul Millerd

Dansk

Danmark