Profits Before Pay

- Af

- Episode

- 45

- Published

- 20. feb. 2012

- Forlag

- 0 Anmeldelser

- 0

- Episode

- 45 of 389

- Længde

- 28M

- Sprog

- Engelsk

- Format

- Kategori

- Fakta

It may come as no great surprise that many of us have experienced a wage squeeze, while the cost of living has gone the other way, since the financial crisis of 2008. However, as Duncan Weldon, a senior economist at the Trades Union Congress, points out, wages for most people in the UK began stagnating years before the crisis.

We tend to think of the early 2000s as a time of relative wealth: house prices were rising, credit flowed easily, the government introduced a generous tax credit scheme and people generally felt better off. But Duncan Weldon argues these masked the reality of what was going on.

Work done by the think tank The Resolution Foundation, which focuses on those on low and modest incomes, shows that there was almost no wage growth in the middle and below during the five years leading up to 2008 and yet the economy grew by 11% in that period. Others also point out that the share of the national income which goes into wages, as opposed to profits, has been decreasing since the mid-1970s. The argument is that less of the economic pie is going into the pockets of ordinary workers.

What is also clear is that a disproportionate amount of the economic wealth has been going to those at the top. The earnings of the richest few per cent have increased rapidly in the UK since the 1980s and that pattern accelerated in the last ten years. In the United States that process began earlier and has been more extreme.

Some economists argue that this is not a problem in itself as taxation, for example, helps to re-distribute the money to the less well off or those with disadvantages.

In Analysis Duncan Weldon asks why wages stopped rising in the years before the crash and what was the driving force for the squeeze?

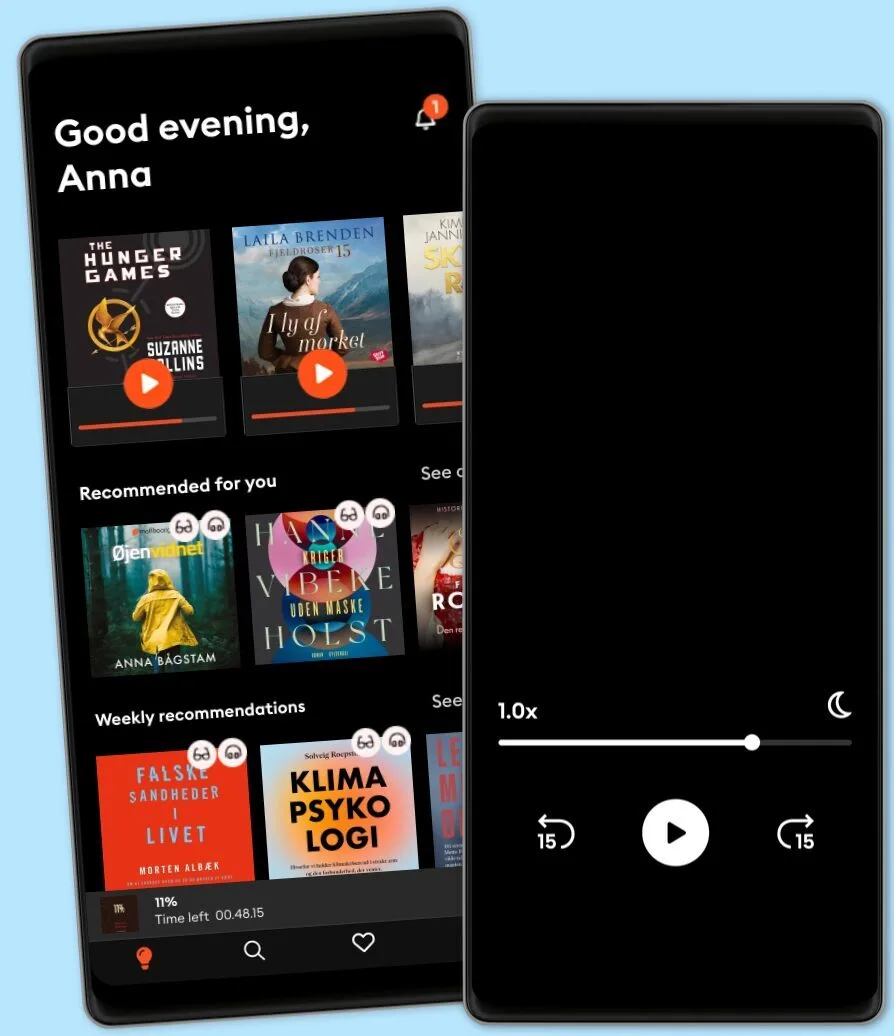

Lyt når som helst, hvor som helst

Nyd den ubegrænsede adgang til tusindvis af spændende e- og lydbøger - helt gratis

- Lyt og læs så meget du har lyst til

- Opdag et kæmpe bibliotek fyldt med fortællinger

- Eksklusive titler + Mofibo Originals

- Opsig når som helst

Other podcasts you might like ...

- M’usa, con l’apostrofo. Le donne di PicassoLetizia Bravi

- FC PopCornFilm Companion

- The Big StoryThe Quint

- DiskoteksbrandenAntonio de la Cruz

- Dragon gateEdith Söderström

- En amerikansk epidemiPatrick Stanelius

- En värld i brand: Andra världskriget och sanningenAnton Vretander

- FamiljenFrida Anund

- Hagen-fallet: Spårlöst försvunnenAntonio de la Cruz

- HelikopterpilotenVictoria Rinkous

- M’usa, con l’apostrofo. Le donne di PicassoLetizia Bravi

- FC PopCornFilm Companion

- The Big StoryThe Quint

- DiskoteksbrandenAntonio de la Cruz

- Dragon gateEdith Söderström

- En amerikansk epidemiPatrick Stanelius

- En värld i brand: Andra världskriget och sanningenAnton Vretander

- FamiljenFrida Anund

- Hagen-fallet: Spårlöst försvunnenAntonio de la Cruz

- HelikopterpilotenVictoria Rinkous

Dansk

Danmark