Why I Turned Down $500k, Shut Down My Startup, And Joined the Enterprise

- Af

- Episode

- 102

- Published

- 4. sep. 2017

- Forlag

- 0 Anmeldelser

- 0

- Episode

- 102 of 256

- Længde

- 25M

- Sprog

- Engelsk

- Format

- Kategori

- Økonomi & Business

Welcome to our 100th show.

If you are new, welcome to Disrupting Japan. If you are a long-time follower, thank you for being part of the community and helping to make Disrupting Japan what it is today.

This is a special, and rather short, episode.

Today I'm going to tell you a very personal story of startup failure, and let you in on what's coming next. Both for me, and for the show.

Thank you for listening, and I think you'll enjoy this one.

[shareaholic app="share_buttons" id="7994466"] Leave a comment

Transcript Disrupting Japan episode 100. Welcome to Disrupting Japan. Straight talk from Japan's most sucessful entreprenuers. I'm Tim Romero and thanks for joining me. Wow. One hundred episodes! That’s right Orson Wells only made 64 movies. The Rolling Stones have only recorded 53 albums. Lord Byron only published 83 poems. But Disrupting Japan has now released 100 episodes. And I’m pretty happy about that. When I started this show, almost exactly three years ago, I never imagined it would grow into the big international community it has become, and I want to thank you for being part of it. Wether you were one of our 14 original listeners or one of the thousands who have signed up more recently, thanks for joining the conversation about some of the truly amazing things going on in Japanese startups and innovation today. I knew I had to do something special for our 100th show, and gave a lot of thought to exactly what that should be. I thought about doing a clip show with many of Japan’s startup founders saying a word about startup in Japan and wishing us a happy 100, but that seems kind of, I don’t know vain and self-congratulatory. I thought about getting a big name on the show. There are a couple of world-famous Japanese founders who I could have probably brought on for the big anniversary, but that didn’t feel quite right either. I mean, we’ll definitely get those guys on later, but what you’ve been telling me — pretty consistently — over the past three years, is that it’s the human stories of success .. and failure and challenge that really meet to matter. And that makes sense. It’s not the dot.com billionaires that are diving innovation in Japan. It’s the thousands of individual innovators and the millions of Japanese people newly willing to take chance and try out these new ideas that are really driving the change. In a way, the billionaires are just as much a result of these historic changes as they are a cause of them. The real change, the real engine for innovation in Japan is the creative people who are willing to take some very real social and economic risks to follow their dreams and try to create something new. I mean, they are not selfless. Very few of them are doing it for the betterment of Japan. No they have their own reasons some financial, some personal, but they are willing to put themselves out there, both economically by starting a company, and socially by, among other things, coming onto this show and talking very frankly about what they feel, and what they fear … and what they really want. This kind of public openness about true hopes and fears. This kind of sharing. It’s never really been a part of Japanese culture, but that’s changing. At least among startup founders. And that’s a great thing. So, in that spirt of openness about failure and success and hopes and dreams, for this special 100th episode, I’ve decided to share a personal story of my own. I’m going to tell you about one of my startup failures, and then I’ll tell you about my new job. I can talk about it now, and if you haven’t heard yet, you are in for a surprise. Ah, but before I tell you about dreams of future success, I owe you a story of past failure. This is adapted from an article I wrote a little more than a year ago about why I decided to shut down my latest startup a few weeks before launch. The article was originally titled “Why I Turned Down $500k, Pissed off my investors, and shut down my startup.” That article went viral. For a while it was the top story on Medium and Pulse. It was reprinted by Venture Beat and Quartz, and many others. It’s been read by over 3 million people and translated into four languages — that I know of. And let me tell you, its strange spending two weeks as the worlds most famous failure. I got more than 4,000 emails and messages during that time. Most were supportive, but the experience was overwhelming and a bit surreal. But I would like to tell the story to you, and as a member of the Disrupting Japan community, I think you will enjoy it, but you will actually —- understand it. You know, a few weeks ago a close friend told me that between my articles and my blog and Facebook and Disrupting Japan and my general oversharing, that I was living my life as some kind of performance art. Now, me being me, I came up with the perfect response to him about a week later, but at the time I just kind of laughed and said something stupid like “Yeah, maybe.” Well, the truth is, we are all living our lives as a kind of performance art. It’s just that most people have not realized it yet. Ah, but I still owe you a story, so let’s her from our sponsor and then get right to it. [pro_ad_display_adzone id="1411" info_text="Sponsored by" font_color="grey" ] I just did what no startup founder is ever supposed to do. I gave up. It wasn’t even one of those glorious “fail fast and fail forward” learning experiences. After seven months of hard work and two weeks before we were to start fundraising, we had a good team, glowing praise from beta users, and over $250k in handshake commitments. But I pulled the plug. My team and most of my investors are pissed, but I’m sure I did the right thing. At least I think I’m sure. The business had what I considered to be an unfixable flaw. My investors and my team wanted us to take the funding and figure out how to fix the problem before the money ran out. I’ve started companies in the past with a mixture of exits and bankruptcies, so I understand that this is what startups are supposed to do, but I just couldn’t do it this time. This is in part my explanation to the various stakeholders, in part self-therapy, and in part a call to other founders and investors to let me know what they would have done in my situation. I began work on ContractBeast, a SaaS-based contract lifecycle management offering, last October. Unless you’ve worked in big IT, you’ve probably never heard of Contract Lifecycle Management or CLM. In brief, CLM covers the authoring, negotiation, execution, and storage of both physical and digital contracts with strict access control. It also does things like let you know what contracts are about to expire or automatically renew, and who is responsible for those deals. CLM is a highly fractured, $7.6 billion global market with over 80 established companies fighting for market share— and that’s not counting the dozens of e-signature startups that have popped up in recent years. Almost all of these companies are clustered in the enterprise space, where sales-cycles are long and top-down, and where revenues are driven by consulting and customization. It’s a big market begging for disruption. The mid-market of small and medium businesses is grossly underserved and the enterprise market is grossly overpriced. ContractBeast was going to deliver a low-cost SaaS product with no consulting required. We would focus on the mid-market first, and then work our way up to the enterprise. [pro_ad_display_adzone id="1652" info_text="Sponsored by" font_color="grey” ] Our target users responded positively to the mock-ups, and many excitedly asked when they could start using it. I was on the right track. I spent the next few months working evenings and weekends developing an MVP and getting feedback on features as they were implemented. I left my job in January so I could work on ContractBeast 70+ hours a week. The rest of the team kept their day jobs. That was fine. It made my final decision easier. We started private beta in early March, and things looked solid. About 35% of our users continued to use the system at least three times per week after completing registration. The UI needed work, but our users raved about how ContractBeast would save them time and worry in the future. The team was excited. Our potential investors were excited. But something was wrong. It seemed trivial at first, but it bothered me. Despite glowing praise, our users were only using ContractBeast to create a small percentage of their total new contracts. I spent the next two weeks visiting our beta users, looking over their shoulders as they worked, and listening to them explain how they planned on using the product. Pressing them directly on why they were not using ContractBeast to create most their contracts resulted in a lot of feature requests. Now, talking with customers about features is tricky. Often you receive solid and useful ideas. Occasionally a customer will provide an insight that will change the way you look at your product. But most of the time, customers don’t really want the features they are asking for. At least not very badly. When users are unhappy but can’t explain exactly why, they often express that dissatisfaction as a series of tangential, trivial feature requests. We received a lot of ideas like integrating alerts with various messaging platforms, using AI to analyze contract content, and building more sophisticated search features. These aren’t necessarily bad ideas, but they had nothing to do with why they were not using ContractBeast more extensively. I might write an article someday on how to tell these tangential feature requests from useful feature requests. Your customers mean well, but implementing these kinds of features will not make your users any happier in the short term. In any event,

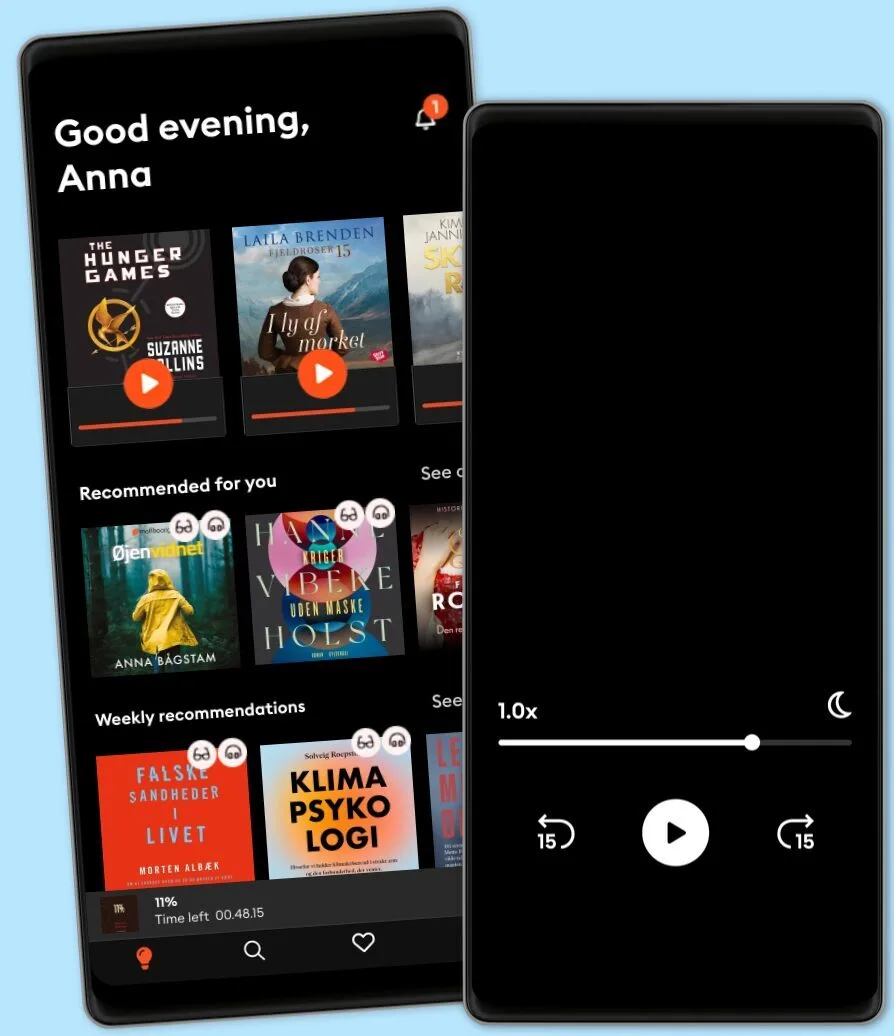

Lyt når som helst, hvor som helst

Nyd den ubegrænsede adgang til tusindvis af spændende e- og lydbøger - helt gratis

- Lyt og læs så meget du har lyst til

- Opdag et kæmpe bibliotek fyldt med fortællinger

- Eksklusive titler + Mofibo Originals

- Opsig når som helst

Other podcasts you might like ...

- The Journal.The Wall Street Journal & Spotify Studios

- The Can Do WayTheCanDoWay

- 1,5 graderAndreas Bäckäng

- Redefining CyberSecuritySean Martin

- Networth and Chill with Your Rich BFFVivian Tu

- Maxwell Leadership Executive PodcastJohn Maxwell

- Mark My Words PodcastMark Homer

- Ruby RoguesCharles M Wood

- EGO NetCastMartin Lindeskog

- The Pathless Path with Paul MillerdPaul Millerd

- The Journal.The Wall Street Journal & Spotify Studios

- The Can Do WayTheCanDoWay

- 1,5 graderAndreas Bäckäng

- Redefining CyberSecuritySean Martin

- Networth and Chill with Your Rich BFFVivian Tu

- Maxwell Leadership Executive PodcastJohn Maxwell

- Mark My Words PodcastMark Homer

- Ruby RoguesCharles M Wood

- EGO NetCastMartin Lindeskog

- The Pathless Path with Paul MillerdPaul Millerd

Dansk

Danmark