The forgotten mistake that killed Japan’s software industry

- Af

- Episode

- 211

- Published

- 9. jan. 2023

- Forlag

- 0 Anmeldelser

- 0

- Episode

- 211 of 256

- Længde

- 33M

- Sprog

- Engelsk

- Format

- Kategori

- Økonomi & Business

This is our 200th episode, so I wanted to do something special.

Everyone loves to complain about the poor quality of Japanese software, but today I’m going to explain exactly what went wrong. You'll get the whole story, and I'll also pinpoint the specific moment Japan lost its way. By the end, I think you'll have a new perspective on Japanese software and understand why everything might be about to change.

You see, the story of Japanese software is not really the story of software. It's the story of Japanese innovation itself.

The Elephant in the Room Japanese software has problems. By international standards, it’s just embarrassingly bad. We all know this, but what’s interesting is that there are perfectly rational, if somewhat frustrating, reasons that things turned out this way. Today I’m going to lay it all that out for you in a way that will help you understand how we got here, and show you why I am optimistic about the future. You see, the story of Japanese software, is not really about software. It's the story of Japanese innovation itself. The ongoing struggle between disruption and control. It’s a story that involves, war, secret cartels, scrappy rebels, betrayal, rebirth, and perhaps redemption. How This Mess Started So let’s start at the beginning. The beginning is further back than you might expect. To really understand how we got here, we need to go back, not just to the end of WWII, but to the years after the Meiji restoration, the late 1800s, back when the Japanese economy was dominated by the zaibatsu. Now, “zaibatsu” is usually translated as “large corporate group” or “family controlled corporate group.” While that is accurate, it grossly understates the massive economic and political power these groups wielded around the turn of the 20th century. Japan’s zaibatsu were not corporate conglomerates as we think of them today. You see, although the Meiji government adopted a market-based economy and implemented a lot of capitalist reforms, it was the zaibatsu, with the full support of the government, that kept the economy running. And the zaibatsu system was almost feudal in nature. The national government could, and did, pass legislation regarding contract law, labor reforms, and property rights, but in practice these were more like suggestions. In reality, as long as the zaibatsu kept the factories running, the rail lines expanding, and the shipyards operating at capacity, the men in Tokyo didn’t trouble themselves too much with the details. In practice, the zaibatsu families had almost complete dominion over the resources, land, and people under their control. They were the law. At the turn of the pervious century, there were four major zaibatsu (Sumitomo, Mitsui, Mitsubishi, and Yasuda). And each zaibatsu had its own bank, its own mining and chemical companies, its own heavy manufacturing company, etc. But it wasn’t just industry, each of these zaibatsu groups had strong political and military alignments. For example, Mitsui had strong influence over the army, while Mitsubishi had a great deal of sway over the imperial navy. At the start of WWII, the four zaibatsu families controlled over 50% of Japan’s economy. This fact, when combined with their political influence, quite understandably, made Japan’s military government very uncomfortable, and during the war, the military wrested away a bit of the zaibatsu’s power and nationalized some of their assets. After Japan’s defeat, the American occupation forces considered the zaibatsu a serious economic and political risk to Japan becoming a liberal, democratic fully developed nation. They targeted 16 firms for complete dissolution and another 24 for major reorganizations. Rising from Ashes Now, that was supposed to be the end of the zaibatsu. I say “supposed to” because those of you who know Japanese history understand that it never really happened. Of course, many things changed. Important political and social reforms were implemented, the legal system was greatly strengthened, a lot of zaibatsu assets were nationalized, and the zaibatsu themselves ceased to be. At least, officially. You see, the zaibatsu were quickly allowed to restructure in greatly weakened , but very familiar, forms, as keiretsu. This was permitted for two main reasons. First, as the cold war heated up in the 40s and 50s, America’s idealistic vision for a democratic and progressive Japan took a back seat to the more practical and pressing need to develop Japan into a bulwark against Communism. And that meant prioritizing economic growth over social reforms. With these new goals in mind, both the American occupation forces and the Japanese government, quite correctly, concluded that having something like the zaibatsu groups would to lead to faster, more predictable growth than tearing everything down and rebuilding from scratch. The second important, and kind of surprising, reason was that almost no one in Japan really wanted to see the zaibatsu broken up. Not the politicians, certainly not the leaders of the zaibatsu, not the public at large, and to the endless frustration and confusion of western labor organizers, not even the rank-and-file zaibatsu workers and employees. In fact, at one point 15,000 Matsushita union members signed a petition demanding that the Matsushita zaibatsu(1) not be broken up. So in the end, important changes were made. Labor rights and contract law were strengthened significantly, and even more zaibatsu assets were confiscated. The traditional family holding companies were dissolved, but they were replaced by cross-company shareholdings and interlocking corporate boards that achieved much the same result, but in a much more transparent and manageable way. And so, most of Japan’s zaibatsu were allowed to morph into the smaller, less threatening, and much more manageable keiretsu. Japan as a Global Innovator In same way that the zaibatsu defined the economic miracle that was Japan’s Meji-era expansion, the keiretsu would come define the economic miracle that was Japan’s post war expansion. Today there are six major and a couple dozen minor keiretsu groups, and during Japan’s economic expansion, as much as possible, they kept their business within the keiretsu family. Projects were financed by the keiretsu bank, the materials and know-how were imported by the keiretsu trading company, and the final products would be assembled in the appropriate keiretsu brand’s factory. And supporting all of these flagship brands were, and still are, tens of thousands of very small, exclusive manufacturers that make up the keiretsu supply chain — and the bulk of the Japanese economy. And with the exception of a tiny handful of true startup companies like Honda and Sony, all of Japan’s brands that were famous before the year 2000 or so, are keiretsu brands. And for those of you who think big companies can’t innovate, let me remind you that from the 50s to the 70s, these keiretsu groups began innovating, disrupting, and dominating almost every industry on the planet; from cars, to cameras, to machine parts, to steel, to semiconductors, to watches, to home electronics, Japan’s keiretsu simply rewrote the rules. But how did the keiretsu do in the world of software development? Well, pretty darn well, actually. It’s important to remember, though, that the software industry in the 60s and 70s was very different than it is today. The software development process itself was actually rather similar. Fred Brooks wrote The Mythical Man Month about his experience during this era, and it remains as one of best books on software engineering and project management today. But the way software was bought and sold was completely different. In the 60s and 70s, software was written for specific and very expensive hardware, and the software requirements were negotiated as part of the overall purchase contract. Software was not viewed so much as a product, but more like a service, similar to integration, training, and ongoing support and maintenance. It was usually sold on a time-and-materials basis, and sometimes it was just thrown in for free to sweeten the deal. The real money was in the hardware. Software in this time (both in Japan and globally) was written to meet the spec. It did not matter if it was creative, innovative, easy to use, or elegant, it just had to meet the spec. In fact, trying to build exceptional software in this era was considered a waste of resources. After all, the product had already been sold and the contracts had already been signed. The goal back then, just like many system integration projects today, was to build software that was just good enough to get the client to sign off on it as complete. Software that met the customer’s spec was, by definition, good software. Japan’s keiretsu did well in the age of big-iron. Although Fujitsu, NEC, and Hitachi never seriously challenged IBM and Univac’s global dominance in the 60s and 70s, they did pretty well in mini-computers and large office systems. They were innovators. Japan Turns its Back on a New Industry However, when the PC revolution arrived in the late 1980s, Japanese industry as a whole was hopelessly unprepared, and not for the reasons you might think. The reason Japanese software development stopped advancing in the 1980s had nothing to do with a lack of talented software developers. It was a result of Japan’s new economic structure as a whole, and the keiretsu in particular. As a market, personal computers were something fundamentally new. Sure, the core technology and the hardware were direct continuations from the previous era, but this new market was completely different. The PC market quickly coalesced around a small number of standardized operating systems and hardware architectures. The keiretsu did pretty well in hardware side of this market, making some really impressive machines, particularly laptops.

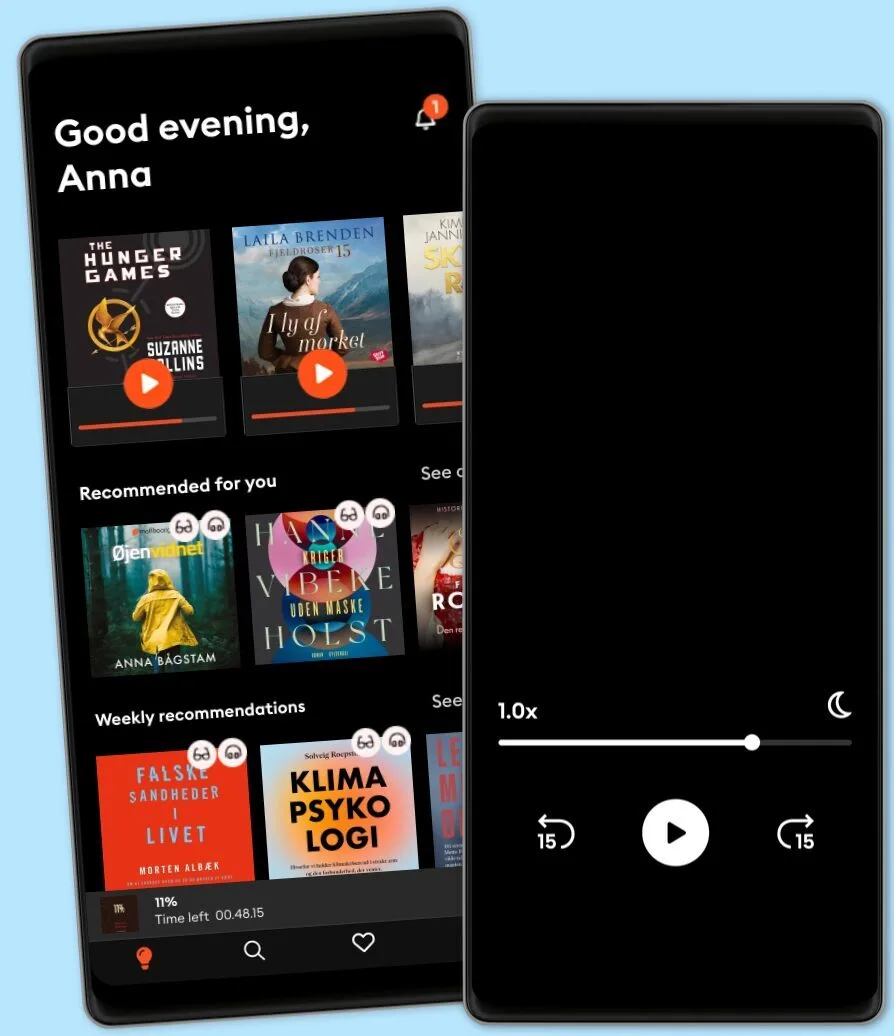

Lyt når som helst, hvor som helst

Nyd den ubegrænsede adgang til tusindvis af spændende e- og lydbøger - helt gratis

- Lyt og læs så meget du har lyst til

- Opdag et kæmpe bibliotek fyldt med fortællinger

- Eksklusive titler + Mofibo Originals

- Opsig når som helst

Other podcasts you might like ...

- The Journal.The Wall Street Journal & Spotify Studios

- The Can Do WayTheCanDoWay

- 1,5 graderAndreas Bäckäng

- Redefining CyberSecuritySean Martin

- Networth and Chill with Your Rich BFFVivian Tu

- Maxwell Leadership Executive PodcastJohn Maxwell

- Mark My Words PodcastMark Homer

- Ruby RoguesCharles M Wood

- EGO NetCastMartin Lindeskog

- The Pathless Path with Paul MillerdPaul Millerd

- The Journal.The Wall Street Journal & Spotify Studios

- The Can Do WayTheCanDoWay

- 1,5 graderAndreas Bäckäng

- Redefining CyberSecuritySean Martin

- Networth and Chill with Your Rich BFFVivian Tu

- Maxwell Leadership Executive PodcastJohn Maxwell

- Mark My Words PodcastMark Homer

- Ruby RoguesCharles M Wood

- EGO NetCastMartin Lindeskog

- The Pathless Path with Paul MillerdPaul Millerd

Dansk

Danmark