How One Good Idea Emerged from Japan’s Nuclear Disaster – Safecast

- Af

- Episode

- 90

- Published

- 5. jun. 2017

- Forlag

- 0 Anmeldelser

- 0

- Episode

- 90 of 256

- Længde

- 47M

- Sprog

- Engelsk

- Format

- Kategori

- Økonomi & Business

After the March 2011 earthquake and the explosions at the Fukushima nuclear power plant, TEPCO and the Japanese government tried to assure us that everything was just fine. The repeatedly insisted that there was no serious danger posed by the radiation.

Not very many people believed them.

Reliable data from fallout areas was sparse at best, and many Japan residents doubted that the government was telling the truth in the first place.

It was in that environment that Pieter Franken and his team created Safecast. Safecast began as a small group in Japan with home-made Geiger counters making their reading available to everyone. They have now grown into an international movement involving private citizens, universities, non-profit organizations and government agencies.

Pieter also explains why environmental science will look very different ten years from now.

It’s a fascinating discussion, and I think you’ll enjoy it.

Show Notes for Startups

Why Japan's disaster preparation failed Why you need high-resolution and high-density radiation monitoring Why citizens do not, and perhaps should not, trust their governments The advantages of creating a DYI kit rather than a product How to maintain data integrity for crowdsourced efforts Why both pro-nuke and anti-nuke activists opposed Safecast How governments have reacted to alternative data sources Safecast's plan to win over the scientific community The future of citizen science

Links from the Founder

Everything you wanted to know about Safecast

Safecast's radiation maps Safecast's radiation report

Connect with Pieter on LinkedIn Follow him on Twitter @noktonlux

[shareaholic app="share_buttons" id="7994466"] Leave a comment Transcript from Japan

Disrupting Japan, episode 89.

Welcome to Disrupting Japan. Straight talk from Japan’s most successful entrepreneurs. I’m Tim Romero and thanks for joining me.

You know, crowdfunding and crowdsourcing in Japan largely gained in its popularity in projects related to the massive March 2011 earthquake, and ensuing tsunami, and the release of radiation at the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant. In fact, longtime listeners have heard the founders of some of Japan’s largest crowdfunding and crowdsourcing companies explain that breaking away from this image of crowdfunding as a social good was something that they had to overcome before their startups became truly successful.

Well, today we’re going to sit down with Pieter Franken of Safecast, one of the earliest examples of widespread crowdsourcing in Japan. And we talk about how they’ve grown from a Japanese patchwork solution to the leader of a global movement. After the Fukushima nuclear disaster, people throughout Japan were worried about radiation. TEPCO, who operated the facilities and the Japanese government assured everyone that things were under control and that everyone was perfectly safe. As you might imagine, however, most people were highly skeptical of these claims. The radiation data just wasn’t there or it wasn’t being shared with the public or it wasn’t believed when it was shared with the public.

Pieter and his team started Safecast to make sure that lack of information and lack of transparency would never happen again and they began building low-cost Geiger counters that people around the country and then around the world could use to measure their local area and then have all that data uploaded into the cloud and made available for anyone. It’s an amazing story and it’s one that Pieter tells much better than I do. So let’s hear from our sponsors and get right to the interview.

[pro_ad_display_adzone id="1404" info_text="Sponsored by" font_color="grey" ]

[Interview]

Tim: So I’m sitting here with Pieter Franken of Safecast. You guys make an open environmental data collection system for everyone but I think you can explain much better than I can what it is.

Pieter: To explain what we’re doing, best thing is just to go back in time a little bit. Exactly six years ago in March 2011, we all witnessed the big earthquake and as part of that, the Fukushima Daiichi disaster. And it’s really where Safecast started. It started from the need to know what was happening in terms of radiation exposure in Japan. Also, the folks that were here will remember very well there was lots of a concern about that but also the biggest problem was there was no data available. Whatever the authorities said was very sparse and most of it was not useful, nothing was really from Fukushima itself. We tried to solve that problem.

Tim: Also as I recall that there was a lot of people that just simply didn’t believe what the government was telling them.

Pieter: Yeah. Lots of people didn’t trust TEPCO’s own assessment. But the real problem I think in retrospect was there was very little information available. Whatever was available was not disclosed. By the sheer fact that information was not available, that created even a bigger distrust. That was really the space where we decided to start Safecast. We said, “We must know what is happening in the environment.” Radiation at that time was the critical driver. We said, “How can we make this as open and transparent as possible?”

We did all kind of things in the beginning. We didn’t start with the soldering iron and building things. We actually thought that information would be available yet it was just hard to find or not easy to digest. So we started to look around on the internet hoping to find all that information and then put it on a website and share that; however, that didn’t really fan out. We didn’t find information. Most of it was from some universities that all were in Tokyo or measuring something that wasn’t relevant. Our MEP was very empty after looking around for two weeks, so started to rethink.

Tim: Did the Japanese government have a unified national data collection system for radiation?

Pieter: Yes and no. They actually had a system. The system was called ‘Speedy.’ That system was originally designed to predict where the plume would go after a nuclear disaster. So it had sensors and it had a huge mainframe with a huge piece of software on it. Then we’d read all the sensor data and then churn out, project the trajectory of the plume.

The key thing is that system was there. It did operate but it is not a publicly accessible system. It’s not that you’re going online and see what is happening here. So the information was exclusively available to Japanese government only. And for all kind of reasons, they decided to ignore that information. So this is one of the big parts of the whole accident that went horribly wrong. So they didn’t look at that information and they started to improvise from that point onwards.

To answer your question, yes, there was a system not publicly available and effectively was not used. Today, that system has been decommissioned. Today, Japan doesn’t have that system anymore. So we actually have less than what we had before the accident.

Tim: Well, hopefully with Safecast we’ve got a more thorough data than we had before.

Pieter: Right. So we realized that information wasn’t available. We couldn’t put on a website so we said, “Okay. Maybe we can crowdsource the data.” The initial idea was to buy Geiger counters and give them to folks so that they could collect the data and tell us so that we could publish that. We did try to do that but shortly after the accident, all Geiger counters worldwide sold out because everybody in Japan needed one. But what we didn’t realize was that they would be sold out for 6 to 12 months because the supply chain for this is not – they’re not iPhones or something where millions can be produced on demand.

Tim: Yeah. I’m sure there’s been a slow steady demand for them.

Pieter: Yeah, yeah. Exactly. So the factories that are churning them out were not going to scale up and were not very easy to scale up because the actual sensors are not so easy to manufacture. So the net-net was there’s no Geiger counters. We had actually run a kickstarted campaign by that time. So we got some money and then we started to rethink. We don’t have Geiger counters. What do we do next? So we had a few Geiger counters that we had. By that time we had maybe 10 or so. The idea was born that maybe we can do what Google does, kind of a street map view of radiation by driving around. That kind of started into something that we thought we could execute. We did a trial. We had a truck driver go up, David Kell. He was one of the volunteers going out by truck. We gave him a Geiger counter and an iPhone and we said, “Whenever you stop, just take a measurement and after you have taken a measurement just upload it.” As he was travelling up north, he kept on sending these pictures up and we could see what was happening. So it was kind of the real first version but it was just to see that you know, would this work? The second version of this was a group of Keio University students, and we were more structured. They were driving up and we said, “Every 5 minutes, take a picture of the Geiger counter.” They kind of duct taped the Geiger counter onto the car on the outside and they were sitting inside. So they could see the screen of the Geiger counter and every 5 minutes they snapped a picture.

Tim: Yeah. In principle, that’s still kind of what you’re doing.

Pieter: That’s what we’re doing. The only thing we did is we automated the process. We had a bunch of people that were at Tokyo Hackerspace. We all got together and we started to say, “How can we make this thing with Arduinos and make it more automated?” So we put the whole thing together. We chose a box to put it all in which looked kind of a bento box. We hooked up a computer and that was kind of the real kind of the first thing we got going.

Tim: So you basically designed a do-it-yourself Geiger counter kit.

Pieter: Right.

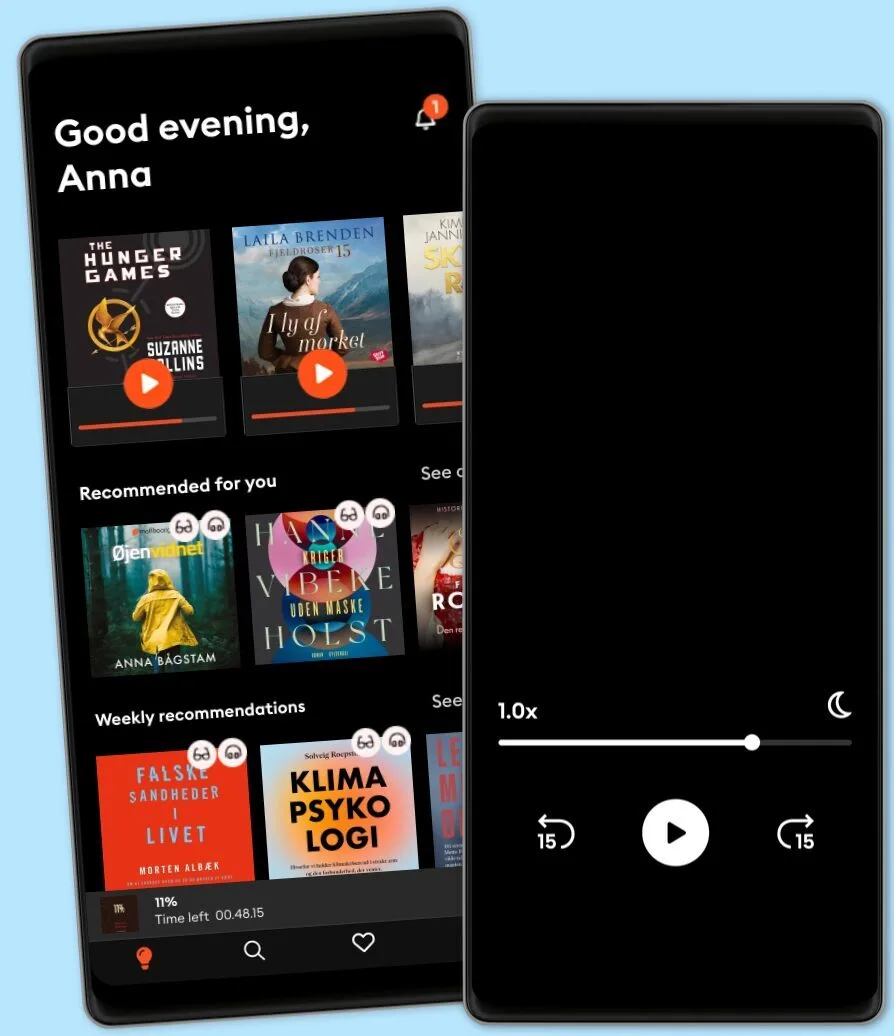

Lyt når som helst, hvor som helst

Nyd den ubegrænsede adgang til tusindvis af spændende e- og lydbøger - helt gratis

- Lyt og læs så meget du har lyst til

- Opdag et kæmpe bibliotek fyldt med fortællinger

- Eksklusive titler + Mofibo Originals

- Opsig når som helst

Other podcasts you might like ...

- The Journal.The Wall Street Journal & Spotify Studios

- The Can Do WayTheCanDoWay

- 1,5 graderAndreas Bäckäng

- Redefining CyberSecuritySean Martin

- Networth and Chill with Your Rich BFFVivian Tu

- Maxwell Leadership Executive PodcastJohn Maxwell

- Mark My Words PodcastMark Homer

- Ruby RoguesCharles M Wood

- EGO NetCastMartin Lindeskog

- The Pathless Path with Paul MillerdPaul Millerd

- The Journal.The Wall Street Journal & Spotify Studios

- The Can Do WayTheCanDoWay

- 1,5 graderAndreas Bäckäng

- Redefining CyberSecuritySean Martin

- Networth and Chill with Your Rich BFFVivian Tu

- Maxwell Leadership Executive PodcastJohn Maxwell

- Mark My Words PodcastMark Homer

- Ruby RoguesCharles M Wood

- EGO NetCastMartin Lindeskog

- The Pathless Path with Paul MillerdPaul Millerd

Dansk

Danmark