How Dancing Satellites from Japan Will Clean Up Outer Space

- Af

- Episode

- 131

- Published

- 17. sep. 2018

- Forlag

- 0 Anmeldelser

- 0

- Episode

- 131 of 256

- Længde

- 40M

- Sprog

- Engelsk

- Format

- Kategori

- Økonomi & Business

There are a lot of aerospace startups in Japan these days. We are seeing innovation in everything from component manufacturing to satellite constellations to literal moonshots.

All of those, however, depend on the ability to place new satellites in orbit, and that is getting harder and harder due to the ever-increasing amount of orbital debris. It's simply getting too crowded up there. Nobu Okada founded Astroscale to solve this problem. Today we sit down and talk about his solution, and we also dive into the very real political and financing challenges that have prevented this problem from being solved.

In many ways, the removal of space debris of a classic Tragedy of the Commons problem. Everyone agrees that it is an important problem that should be solved, but no one wants to spend their own money to solve it.

Well, Nobu and his team have developed a business model that they believe will be able to address this problem. It's an innovative and important approach. And yes, we also talk about dancing satellites. It's a great conversation, and I think you'll enjoy it.

Show Notes

What is this Kessler Syndrome and why do we need to worry about it Why dreams of being an astronaut did not work out Why aerospace startups need their own manufacturing facilities How to bring down a satellite The trigger leading world governments to finally get serious about space clean up What are your options when your satellite fails to launch The single biggest risk in the space debris removal business Why there are so many aerospace startups in Japan recently

Links from the Founder

Check out Astroscale and watch the dancing satellites for yourself Friend them on Facebook Follow Nobu on Twitter @nobuokada

Leave a comment Transcript Welcome to Disrupting Japan, straight talk from Japan’s most successful entrepreneurs.

I’m Tim Romero and thanks for joining me.

There are a surprising number of new aerospace startups in Japan and today, you will be meeting the founder of one of the most innovative one. Nobu Okada founded Astroscale to solve the problem with space debris.

You see, every year, we are putting more and more satellites into orbit, and it’s gotten kind of crowded up there. There are zombie satellites that we have lost control over and there are satellites that have collided, resulting in thousands of small pieces of debris zipping around in random orbits at thousands of miles per hour, just waiting to crash into other satellites and begin a chain reaction.

Well, Nobu and the team want to do something about that. They have a plan to start de-orbiting this debris, and the technology side is fascinating. I mean, you might think that you have no real desire to know how to de-orbit a satellite, but trust me, you want to know how to de-orbit a satellite. It is really that cool.

Of course, Nobu and I cover much more than the technology. A big part of the story is how Astroscale has begun to build international recognition and consensus, and how they have actually constructed a business model around debris removal, and we also talk about the forces driving the sudden growth of aerospace startups and talk a bit about dancing satellite, but you know, Nobu tells that story much better than I can, so let’s get right to the interview.

[pro_ad_display_adzone id="1404" info_text="Sponsored by" font_color="grey" ]

[Interview]

Tim: We are sitting here with Nobu Okada, the CEO and founder of Astros scale was cleaning up space, so thanks for sitting down with us.

Nobu: It is a great pleasure to meet with you and thank you for this great opportunity to be on your podcast.

Tim: I’m delighted to have you, and I’ve got to say, Astroscale is not like your typical startup. You have a really unique mission, so can you kind of explain what your vision is and what you are trying to do?

Nobu: Our mission is to secure long-term space flight safety by removing the space debris, so space debris is jumping space. They are made of rocket upper bodies and old satellites, and fragments caused by the explosion, the collision among them.

Tim: How much space debris is up there?

Nobu: There are a variety of sizes of debris. If we count the object which is larger than 10 cm, there are more than 23,000, and the bigger ones are like, 8 m, 10 m, like a double-decker bus.

Tim: Okay, so it’s quite a range of sizes?

Nobu: Yeah, the small one is like, 1 mm, less than 1 mm, so yeah, it is a wide range.

Tim: And even like a 1 mm sized object can do a tremendous amount of damage to a satellite or a spacecraft.

Nobu: Yeah, right, they are flying with 7 to 8 km/s which means 40 times faster than the Bullet, and so it is quite fast, and they have a huge power to blow up other objects in space.

Tim: Part of the problem as I understand it is that space debris kind of multiplies on its own, that these larger objects will collide with each other and make more and more smaller objects, and the worst-case scenario is of the Kessler condition where there’s so many of these tiny objects, it becomes extremely difficult to launch a satellite or to launch a rocket.

Nobu: Yeah, that’s right. The density of the space debris has reached a certain threshold where what you said, it’s Kessler syndrome which is kind of the situation where a chain reaction of the collision happens. We already reached that threshold, so it is kind of a consensus among the space industries that we should remove large objects now before they get smaller.

Tim: Okay, so we are really at that tipping point where if we don’t do something now, we won’t be able to do anything in the future.

Nobu: That’s right. There are so many discussions and papers, research works when we would not be able to use the space anymore, and we don’t know; it all depends when catastrophic collisions happen. We don’t know, it might happen 100 years later or today, we don’t know. So, we should develop the technologies, business model, and regulations ready for removing the debris.

Tim: Okay. I want to get into the details of exactly how Astroscale is doing this and the challenges you’re facing, but before that, I want to talk a little about you. You founded Astroscale back in 2013 and at that time, you had no background in aerospace at all, so what attracted you to this problem and what was the trigger that made you decide, I’m going to start a startup to remove space debris?

Nobu: When I was 15, I went to NASA in America. There was a space camp program where we can have kind of a junior training to become astronauts. It’s kind of a fun and entertainment.

Tim: I remember space camp well. I wanted to go so bad when I was a kid. I never had the chance.

Nobu: But it’s fun. It’s fun and I met with real astronauts and NASA engineers, and they ignited a passion within my mindset, but what I found, there is no astronaut’s job – physician can be an astronaut, or a pilot can be an astronaut, but there’s no astronaut’s job.

Tim: So, they take someone who’s got the necessary specialty, and in the train that person to be an astronaut?

Nobu: Right. Right, that’s right. So, what I learned is I have to have some major and specialty somewhere else, and then change my career path toward astronaut, and then I went to the government, the Japanese Minister of Finance and I was working for a consulting firm. I ran two IT companies.

Tim: Well, this seems like an unusual path to become an astronaut. I mean, they don’t send out too many management consultants or financial types.

Nobu: I was almost forgetting about that, and then when I turned 40, when I was 39, I came to midlife crisis, kind of a typical situation where people feel about what should we do. I have several people who I respect, and then they did something good during their 40 years, but when I was 39, I had no idea what should I do during my 40s? All of a sudden, I remember the days in NASA, space. Space is something I really wanted to do. At the time, I had been running an IT company for 10 years, I had been dedicated into software industry. I felt like I really want to work on hardware too, and that keyword: space, and then I attended a couple of the space conferences to see what are the hot topics, and then I found that space debris was a growing threat, and then there was a space debris conference – I mean, dedicated for space debris in Germany in 2013, April, and what I saw were research concept simulations. I didn’t see any actions.

Tim: Yeah, well, I think the aerospace in general and space in particular is very much in the old decades long government research financing cycle. I can understand your attraction to the problem and thinking okay, we can apply modern business methods in modern start of initiatives to this seemingly intractable problem, but once you have that motivation, what is your next step? I mean, did you start talking to researchers? How did you get your technical team together, so you could credibly address this problem?

Nobu: I had a wide range of options. I can join the space agency, or I can be an independent consultant to advocate to this issue, or I can go to the university, and graduate school, and to study again, or I start up and give solutions. I had no idea about engineering. If you Google supply development – how to develop supplies – there’s nothing, actually. There is so many papers coming up but it’s very hard to understand.

Tim: Yeah, yeah. I mean, it is an incredibly specialized field.

Nobu: Right. So, what I did is I got CD-ROMs from the space conferences printed out and I read all the papers.

Tim: Just hundreds of papers?

Nobu: 700.

Tim: Wow, okay.

Nobu: I had intensive readings for 300. First reading, I got stuck in each jargon, and I tried to read through again and again. I got all the jargons in the end, and then I came up with hypotheses how to solve this issue,

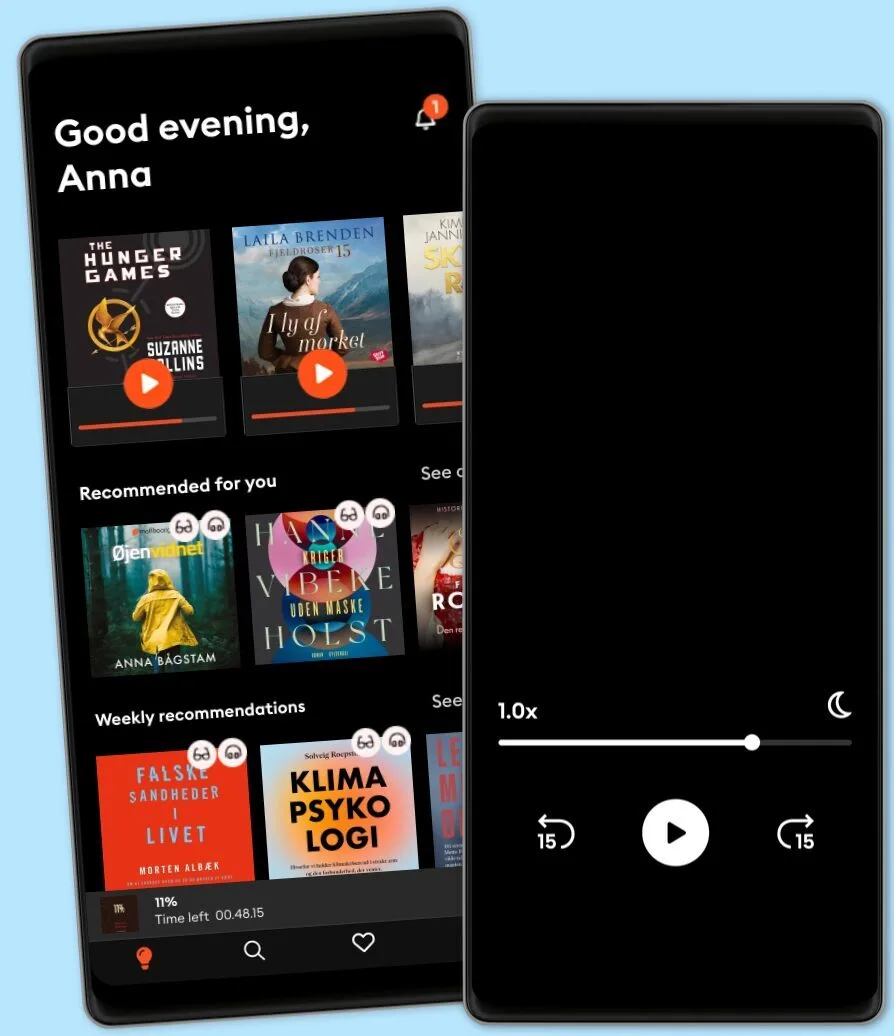

Lyt når som helst, hvor som helst

Nyd den ubegrænsede adgang til tusindvis af spændende e- og lydbøger - helt gratis

- Lyt og læs så meget du har lyst til

- Opdag et kæmpe bibliotek fyldt med fortællinger

- Eksklusive titler + Mofibo Originals

- Opsig når som helst

Other podcasts you might like ...

- The Journal.The Wall Street Journal & Spotify Studios

- The Can Do WayTheCanDoWay

- 1,5 graderAndreas Bäckäng

- Redefining CyberSecuritySean Martin

- Networth and Chill with Your Rich BFFVivian Tu

- Maxwell Leadership Executive PodcastJohn Maxwell

- Mark My Words PodcastMark Homer

- Ruby RoguesCharles M Wood

- EGO NetCastMartin Lindeskog

- The Pathless Path with Paul MillerdPaul Millerd

- The Journal.The Wall Street Journal & Spotify Studios

- The Can Do WayTheCanDoWay

- 1,5 graderAndreas Bäckäng

- Redefining CyberSecuritySean Martin

- Networth and Chill with Your Rich BFFVivian Tu

- Maxwell Leadership Executive PodcastJohn Maxwell

- Mark My Words PodcastMark Homer

- Ruby RoguesCharles M Wood

- EGO NetCastMartin Lindeskog

- The Pathless Path with Paul MillerdPaul Millerd

Dansk

Danmark