How a Rumor Can Destroy Your Business in Japan

- Af

- Episode

- 135

- Published

- 29. okt. 2018

- Forlag

- 0 Anmeldelser

- 0

- Episode

- 135 of 256

- Længde

- 36M

- Sprog

- Engelsk

- Format

- Kategori

- Økonomi & Business

Japanese thoughts on risk are changing, but they are changing slowly.

Many people still consider failure to be a permanent condition, and that makes it hard to take risks, or in some cases even to be associated with risks.

Today we talk with Hajime Hirose, one of Japan's new breed of serial entrepreneurs. Hajime has started companies in three different countries and several different industries. We talk about the challenges and importance of going global and how a Japanese founder ended up running a Chinese company that IPOed in New York.

And of course, we also talk about how difficult it is for startups to combat rumors in Japan, even when everyone knows those rumors to be false.

It's a great conversation, and I think you'll enjoy it.

Show Notes

The road to China runs through Seattle Today's management crisis in Chinese and Indian companies Why leave Japan to start a startup Why not all publicity is good publicity in Japan Why the truth cannot fix lies How to survive when your competition is giving away their product for free What startups are best started outside Japan

Links from the Founder

Connect with Hajime on LinkedIn Hajime's latest project, Datadeck PTMind's PT Engine

Leave a comment Transcript Welcome to Disrupting Japan, straight talk from Japan’s most successful entrepreneurs.

I’m Tim Romero, and thanks for joining me.

You know, there aren’t many serial entrepreneurs in Japan. The reason for that is, well, the same reason why we don’t have a lot of angel investors in Japan. Until very recently, the idea of both startup success and startup failure was permanent.

If your startup succeeded, you were expected to be running it until either you or the company expired, and if you failed, well, if you failed, you were done. Until very recently, failure was considered a permanent condition. No one was inclined to give you a second chance, but things are changing, and today, I would like to introduce you to Hajime Hirose, a Japanese serial entrepreneur who has built and sold startups and also bankrupted them.

We talk about how Japanese attitudes towards startups are changing, but how in Japan, a bad rumor, even a completely unfounded rumor can kill and otherwise promising startup. We also talk about the importance and the difficulty of going global, and the unlikely tale of a Japanese man running a Chinese startup that ended up IPOing in New York, and we also talk about Hajime’s old startup story that wheezed its way through London, Shanghai, Redmond, Jakarta, and yes, of course, Tokyo.

But you know, Hajime tells that story much better than I can, so let us get right to the interview.

[Interview]

[pro_ad_display_adzone id="1411" info_text="Sponsored by" font_color="grey" ]

Tim: Cheers!

Hajime: Cheers!

Tim: All right, so I am sitting here with Hajime Hirose, the what the future founder of BuzzElement, and a few other startups as well, so thanks for sitting down with me.

Hajime: Well, thank you. I’m really excited because I’m a big fan of your show and I’m really thrilled to be on this side of the show.

Tim: Well, listen, I’m excited to have you here because there are relatively few serial entrepreneurs in Japan. So, I’m looking forward to this conversation. Your first real international business was in China, but before we get to that, let us back up and talk about how you wound up there.

Hajime: So, I was born in Tokyo, grew up in Yokohama, and I went to CIO for university, and I’ve been living outside of Japan for the last 26 years.

Tim: And, you ended up working for Microsoft, right?

Hajime: That’s right.

Tim: Back when MSN was still a thing.

Hajime: That’s right, yeah. So, that was back when Microsoft just bought Hotmail back in 1998.

Tim: Oh, the good old days.

Hajime: Yeah, that was good, that was really fun. So, I was lucky to be the only two Japanese guys on the project. My job was to grow with the project, so I was setting up the testing summers and writing tools, so that other people around the world can test it out.

Tim: So, how did you wind up in China?

Hajime: So, I worked for Microsoft for 10 years, from 1998 to 2008. Back in 2004, Microsoft decided that we need to go to China in order to secure more talents. My propriety was to hire a talent and also try to – so, my boss, right? He was a Caucasian guy. He thought I looked Chinese enough. He talked that I speak were spoke Chinese.

Tim: Really? Please, tell me not.

Hajime: No, I don’t know, I don’t know, but yeah, they sent to me there, right? So, during the week, I am one project, but then on weekends, I go around the universities around China to interview people and hire people. I get to meet a lot of smart people and I bring the men.

Tim: How many people were they trying to hire?

Hajime: Our plan was to hire 200 people within two years.

Tim: Okay, that’s aggressive.

Hajime: I did that.

Tim: But, you eventually left to join a Chinese company.

Hajime: That was back in 2007. That was when iPhone just came out and App Store just came out, and I thought, oh, wow, this is it, right? I thought, this is my chance where I can actually do my own startup. So, even before that, I have been wanting to do my own startup, but I was a little bit hesitant.

Tim: So, your plan was to do a startup in China or to go back to the US into a startup?

Hajime: I wasn’t thinking deep enough. I just knew that I want to do a startup somewhere. So, I bought my iPhone and Mac, and my friend, we went to Silicon Valley to visit VCs. I developed some app and showed it to the VC. I think they like the idea in general, but then other people find out that I was trying to leave Microsoft, so I got a headhunting offer from five companies.

Tim: So, these were Chinese companies?

Hajime: Technically, it was a Chinese company. It was all run by Chinese-Americans.

Tim: But, I mean, they were companies in China.

Hajime: Yeah, okay, that’s right, that’s right, yeah, and they said that they will give me a pre-IPO stock which was really attractive for me, and also, I used to manage the engineering team, but I didn’t really manage the whole company. With this job, I was able to manage the whole company. Of course, a subsidiary of that big company, but I get to manage the sales team and HR, and everything. I thought that that was a good experience that I could get.

Tim: Well, what did the company do?

Hajime: All right, so it was an IT solution company.

Tim: So, system integrator?

Hajime: That’s right, yeah. Do you know a company called Infosys?

Tim: Yeah, of course, Sriram is a friend who has been on the show.

Hajime: Oh, really? All right, so VanceInfo was the Infosys of China.

Tim: And, they put you in charge of market entry in Europe, right?

Hajime: Yes. So, when I got hired, I was in charge of the Software and Service group, so my clients were like, Nokia, Microsoft. I was able to grow this company three times, and then we went IPO on the New York Stock Exchange. Now, they need to expand even further, right? They sent me, a Japanese guy, the Europe.

Tim: I see a pattern here and is kind of a confusing one. So, you are working for Microsoft, this American company that sends you to try not to do market entry, and then from China, they sent you to Europe to market entry. So, you are market entering into these markets you know nothing about?

Hajime: Yeah, I guess I’m a firefighter.

Tim: You are a fast learner, that is for sure. You were telling me before that this company, after their IPO, had some management challenges.

Hajime: Before we IPO, we need to globalize our seIf, so, we brought in a global talent from the US, VP of sales, and stuff like that, but they could not really adapt into our culture because our core was so… I don’t know how to say it… Single-minded?

Tim: This is something that Indian companies have a real problem with. Japanese companies used to have a big problem with, and it would be interesting if China is going through the same thing now. Let us talk about Japan because here we are, but Japanese companies, until very recently, were famous for having all of the top decision-makers the Japanese, all of the key decisions being made in Japanese, and it being very hard for anyone who is non-Japanese, no matter how qualified to really be part of the company. Is that the same thing that these Chinese companies are seeing?

Hajime: Yeah, that’s exactly what happened. Even when we brought in a very talented salesperson from the US, on the C levels, we have a heated discussion and they talked in Chinese and we feel like we don’t belong there, and we feel like we are excluded in the boy’s group, I guess. So, that was a lesson that I learned: if you want to build a truly globalized company, I think you need to build a DNA as a global company from the get-go. Otherwise, it’s going to be very hard to change later on.

Tim: These days we see a lot of Japanese companies doing that.

Hajime: Hiring foreigners from the beginning?

Tim: Hiring foreigners, being more inclusive from the beginning.

Hajime: I don’t see many, but maybe more.

Tim: Well, let’s just look at both of the extremes. I think there’s a lot of startups that because there’s so much for an engineering talent available, very early on, they will say, “Okay, we’re going to be multicultural. We’re going to be open to all languages and we will be bilingual internally,” and if you do it from day one, it is much easier to maintain, but I think we have also seen larger Japanese companies, like Uniqlo and Rakuten who have adopted English-only policies. We have seen companies like, okay, maybe this isn’t the best result, but like, Olympus, Matsuda were bringing in very senior foreign president and board members. So, I wonder if that’s something that the Chinese companies and some of the Indian companies,

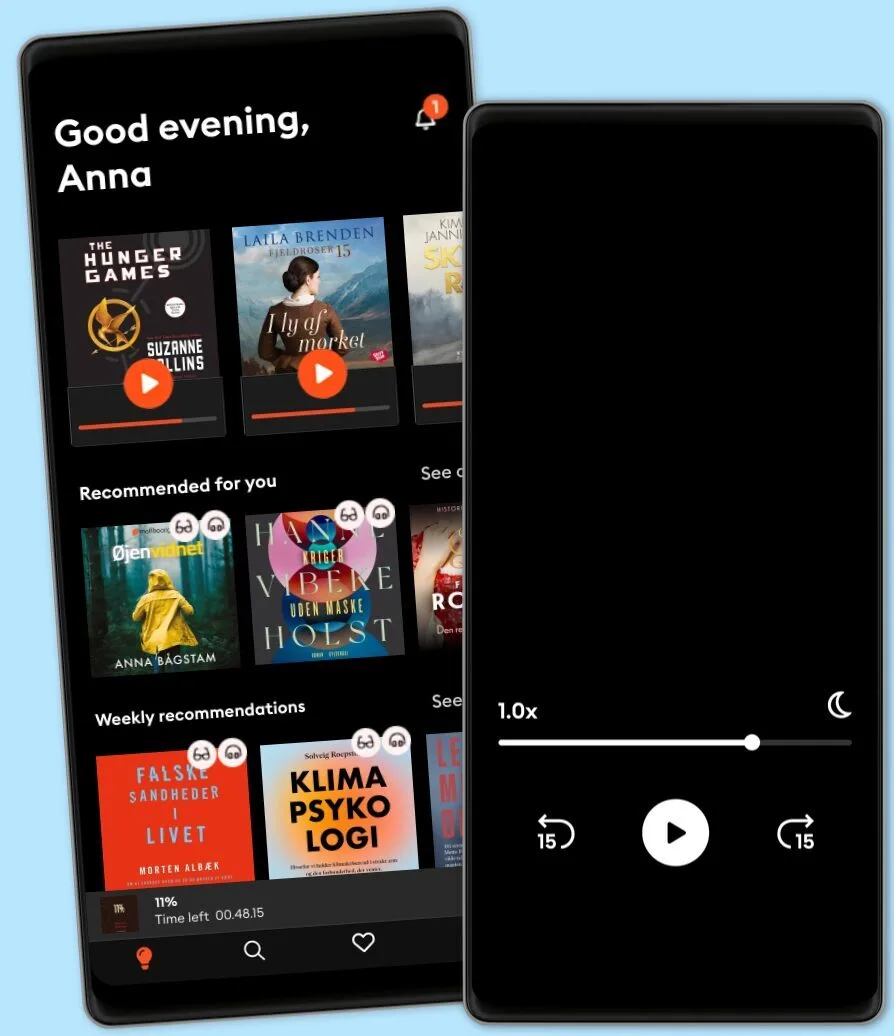

Lyt når som helst, hvor som helst

Nyd den ubegrænsede adgang til tusindvis af spændende e- og lydbøger - helt gratis

- Lyt og læs så meget du har lyst til

- Opdag et kæmpe bibliotek fyldt med fortællinger

- Eksklusive titler + Mofibo Originals

- Opsig når som helst

Other podcasts you might like ...

- The Journal.The Wall Street Journal & Spotify Studios

- The Can Do WayTheCanDoWay

- 1,5 graderAndreas Bäckäng

- Redefining CyberSecuritySean Martin

- Networth and Chill with Your Rich BFFVivian Tu

- Maxwell Leadership Executive PodcastJohn Maxwell

- Mark My Words PodcastMark Homer

- Ruby RoguesCharles M Wood

- EGO NetCastMartin Lindeskog

- The Pathless Path with Paul MillerdPaul Millerd

- The Journal.The Wall Street Journal & Spotify Studios

- The Can Do WayTheCanDoWay

- 1,5 graderAndreas Bäckäng

- Redefining CyberSecuritySean Martin

- Networth and Chill with Your Rich BFFVivian Tu

- Maxwell Leadership Executive PodcastJohn Maxwell

- Mark My Words PodcastMark Homer

- Ruby RoguesCharles M Wood

- EGO NetCastMartin Lindeskog

- The Pathless Path with Paul MillerdPaul Millerd

Dansk

Danmark